Who is Norman Rockwell, Lana Del Rey's Latest Reference?

What does Lana Del Rey’s latest reference tell us about herself, America, and contemporary culture?

Cover photo: Norman Rockwell (undated). Photo via Artsy and Bettmann/Getty Images. (Edited)

WARNING: The following article features and/or discusses expletives, politics, and nihilism.

“Paint me happy and blue, Norman Rockwell,” Lana Del Rey croons in Venice Bitch, a song from her latest album, Norman Fucking Rockwell! Just released August 30th, NFR! is Del Rey at her very best; her vocals feel more powerful, more emotional, and more seductive than ever. Her classic themes of love and America are refined, distilled, particularly potent. But who the fuck is Norman Rockwell?

Since her debut, Lana Del Rey — born Elizabeth Grant — has existed as a pastiche of America, freely quoting famous writers, citing celebrities, and combining cliches. In her song Body Electric (whose very title is a reference to a poem by Walt Whitman), Lana declared, “Elvis is my daddy / Marilyn’s my mother / Jesus is my bestest friend.” It’s only appropriate that Del Rey invokes the 20th century American artist Norman Rockwell for her latest album.

Norman Rockwell in his studio with “Murder in Mississippi”, taken by an unknown photographer (1965). Via Google Arts & Culture.

Freedom from Want, oil on canvas, by Norman Rockwell (1943). Via Norman Rockwell Museum Collections. ©SEPS: Curtis Licensing, Indianapolis, IN.

Rockwell was a commercial artist known for his idealized — often humorous and sentimental — portrayals of America, populated by rowdy dogs, cheerful children and honest citizens. Rockwell’s art reached millions of people. He illustrated over 300 covers for The Sunday Evening Post alone.

Rockwell was considered a populist artist, creating work that celebrated Middle America. Rockwell, whose family came from poverty, became a national icon, synonymous with American life and even the American dream. His success could be ascribed — at least partially — to the fact the bulk of his art was apolitical. Rockwell was himself an independent voter (he leaned liberal) and he was appreciated by politicians on both sides of the aisle.

On Leave, cover for The Saturday Evening Post, by Norman Rockwell (1945). Via The Saturday Evening Post.

Santa’s Helper, cover for The Saturday Evening Post, by Norman Rockwell (1947). Via The Saturday Evening Post.

Soda Jerk, cover for The Saturday Evening Post, by Norman Rockwell (1953). Via The Saturday Evening Post.

Runaway, cover for The Saturday Evening Post, by Norman Rockwell (1958). Via The Saturday Evening Post.

Rockwell painted portraits of several U.S. Presidents including Kennedy and Nixon. In 1977, President Gerald Ford awarded Rockwell the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor. An accompanying certificate read, “Norman Rockwell has portrayed the American scene with unrivalled freshness and clarity. Insight, optimism, and good humor are the hallmarks of his artistic style. His vivid and affectionate portraits of our country and ourselves have become a beloved part of the American tradition.”

As media theorist and author Marshall McLuhan wrote, “We look at the present through a rear-view mirror. We march backwards into the future.” Today Rockwell’s wholesome vision of a kind and honest America is considered the perfect antithesis to a contemporary culture characterized by alternative facts, political polarization, and intense vitriol. Perhaps it is images of Rockwell that voters imagined when in tandem they shouted President Trump’s populist appeal, “Make America great again!”

Rockwell’s art has become a symbol of the idealized American past but is it appropriate to compare Rockwell’s art to contemporary America? Rockwell never intended his art to function as an accurate depiction of the world. He wrote in 1960, “The view of life I communicate in my pictures excludes the sordid and ugly. I paint life as I would like it to be.”

Statue of Liberty, oil on canvas, by Norman Rockwell (1946). Via the White House Historical Association.

President Barack Obama and president-elect Donald Trump in the Oval Office, with a Rockwell painting on the left (2016). Photo taken by Pablo Martinez. Monsivais/AP. Via The Guardian.

Rockwell was a skilled narrative painter, whose art often depicted fictional — though relatable — scenes. Take, for instance, the painting Statue of Liberty in which men can be seen working on the titular sculpture’s flame. According to the White House Historical Association, no repairs were taking place at the time of the painting’s creation and that Rockwell likely chose the subject as “a fitting image for the first Independence Day following the end of the Second World War in August 1945.” Ultimately, the work is fiction manufactured for a compelling patriotic purpose.

During his tenure, President Obama displayed two Rockwell paintings in the White House, including Statue of Liberty. In our polarized political climate, the simple presence of the painting during a meeting with — then president-elect — Donald Trump was read as a scathing rebuke of the incoming president by none other than Rockwell’s own granddaughter, Abigail Rockwell.

Abigail Rockwell argued that Obama’s staff silently moved the painting in effort to condemn Trump’s harsh words against immigrants and minorities. She wrote, “Most of my grandfather Norman Rockwell’s paintings are about tolerance, unity and the inherent goodness and resilience of the human spirit. […] Perhaps they are able to say what Obama could not in these circumstances of necessary protocol.”

The painting’s move proved prophetic, as Trump official Ken Cuccinelli (acting director of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services) has since attempted to revise the Statue of Liberty’s century old inscription by American poet Emma Lazarus, asserting that America should only welcome immigrants “who can stand on their own two feet and who will not become a public charge.”

This revisionism is emblematic of the Trump Administration’s iconoclasm. Donald Trump ran a campaign that promised to “drain the swamp” as a threat to the political establishment and he has since departed from traditions and norms. The global success of populist leaders such as Trump along with the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union (Brexit) can only be read as the international expression of an ultimate skepticism of authority.

Hugo Drochon, author of Nietzsche’s Great Politics, explains “that is where we are today — there’s a rejection of elites, of the establishment, of authority itself. This is dangerous because there’s a kind of nihilism behind it. There’s not really a positive project that comes out of it. It’s just a resounding “no” and it’s not clear what comes next.”

“God is dead! God remains dead! And we have killed him!” wrote 19th century agnostic German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. This was an observation that the progression of science and secular reason could not justify the existence of god and that morality and meaning would have to be based in something other than a divine power.

Nietzsche warned that this skepticism of authority had the potential to evolve into nihilism. “He feared the death of God would result in an era of mass politics in which people sought new “isms” that would give them a group identity,” writes author Sean Illing.

Rockwell himself was not a churchgoer and he rarely included religious content in his art. In fact, Karal Marling, author of Rockwell’s Christmas, explains, “Norman Rockwell is generally credited with the invention of the modern American Christmas […] to create the outlines of a secular, commercial holiday” that exists today.

A rare exception in Rockwell’s oeuvre is his 1951 painting Saying Grace, which depicts an old woman and a young boy silently praying at a restaurant table. The focus of the scene is the bystanders, watching the two figures in their moment of reverence. “The people around them were staring, some surprised, some puzzled, some remembering their own lost childhood, but all respectful,” wrote Rockwell. Saying Grace was featured on The Saturday Evening Post and it was voted by readers as the most popular of his covers.

The American Dream — defined as children enjoying a greater income than their parents — drastically faded during Rockwell’s lifetime. A 2016 study of absolute income mobility determined that 90% of children born in the 1940s earned more than their parents while just 50% of children born in 1980 surpassed their parents (Rockwell died in 1978).

Alarmingly, the study notes, “Absolute income mobility has fallen across the entire income distribution, with the largest declines for families in the middle class.” Surely, this decline has cultural and political implications.

Upon her mainstream debut back in 2012, Del Rey captured this nihilist zeitgeist with her first major-label album which was succinctly titled Born to Die. Born to Die maintains its relevance. In 2018, it became one of just three albums by women with 300 weeks on the Billboard 200 Chart.

In the track Gods & Monsters from Paradise (released later that same year), Del Rey — herself a devout Catholic — sang, “I don’t really wanna know what’s good for me / God’s dead, I said ‘baby that’s alright with me’.” Lyrics like these easily appeal to younger Americans suffering through underemployment, student loan debt, and a gamified gig economy.

A new landmark study identifies chaos and nihilism as pervasive feelings in contemporary American politics. 40% of Americans surveyed agree with the statement that “When it comes to our political and social institutions, I cannot help thinking ‘just let them all burn’.” Unsurprisingly, this electorate favors candidates who are perceived as anti-establishment.

One of the study’s authors, Michael Bang Petersen, notes “that the ‘need for chaos’ correlates positively with sympathy for Trump but also — although less strongly — with sympathy for [Bernie] Sanders. It correlates negatively with sympathy for Hillary Clinton.”

Until the election of President Trump, Lana Del Rey remained apolitical. Del Rey since announced that she was reconsidering her use of the American flag and she spoke out after artist and friend Kanye West embraced the 45th President. On Instagram, Del Rey wrote, “Trump becoming our president was a loss for our country but [Kanye’s] support of him is a loss for the culture.”

About Norman Fucking Rockwell!, Del Rey explains, “It was weird how that actual title came to me. I was riffing over a couple of chords that [producer and co-writer] Jack [Antonoff] was playing for the title track, which ended up being called “Norman Fucking Rockwell.” It was kind of an exclamation mark: so this is the American dream, right now. This is where we’re at—Norman fucking Rockwell. We’re going to go to Mars, and [Donald] Trump is president, all right.”

Del Rey has evolved much since Born to Die in 2012 (a significant tonal shift can be noticed in her 2017 album Lust for Life) but in the NFR! track The Greatest, Del Rey’s music reaches an apocalyptic crescendo. She laments, “The culture is lit and if this is it, I had a ball / I guess that I’m burned out after all,” later adding, “L.A. is in flames / it’s getting hot / Kanye West is blond and gone / “Life on Mars” ain’t just a song.”

Del Rey employs West as an obvious proxy for the current president. In an interview, she asserts, “The President is a reflection of the culture, the culture is a reflection of our relationship with ourselves and, of course, nature is our great reflector and equaliser. Maybe that’s a bit metaphorical but it’s probably no coincidence that it’s raining fire everywhere. I read a caption about the Amazon [rainforest] that said the lungs of our world are burning. It makes me wonder what’s our heart?”

The Final Impossibility: Man’s Tracks on the Moon (Two Men on the Moon), oil on canvas, by Norman Rockwell (1969). Via the Berkshire Edge.

In 1968, after he was invited by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to document man’s first steps on the moon, Norman Rockwell posed the following questions about the Space Race to his friends: “First, why do we do it? Is it to keep up with Russia, or to find new worlds? Is it because of humanity’s instinct to aspire? Second, would it be better to put all this thought, energy and money to improving conditions here on Earth?”

In the wake of our global environmental and political crisis, American billionaires Jeff Bezos of Amazon and Elon Musk of Tesla have inspired countless news headlines about their competing plans to colonize the planet Mars. The obsession with Mars seems to be wishful escapism disguised as human progress. Former NASA chief scientist, Ellen Stofan has said, “I don’t see a mass transfer of humanity to Mars, ever,” adding, “Job one is to keep this planet habitable.”

POP Newsweek Magazine Cover, by Roy Lichtenstein (1966). Via Ignored Prayers.

Norman Fucking Rockwell!, album art (2019). Via Vogue.

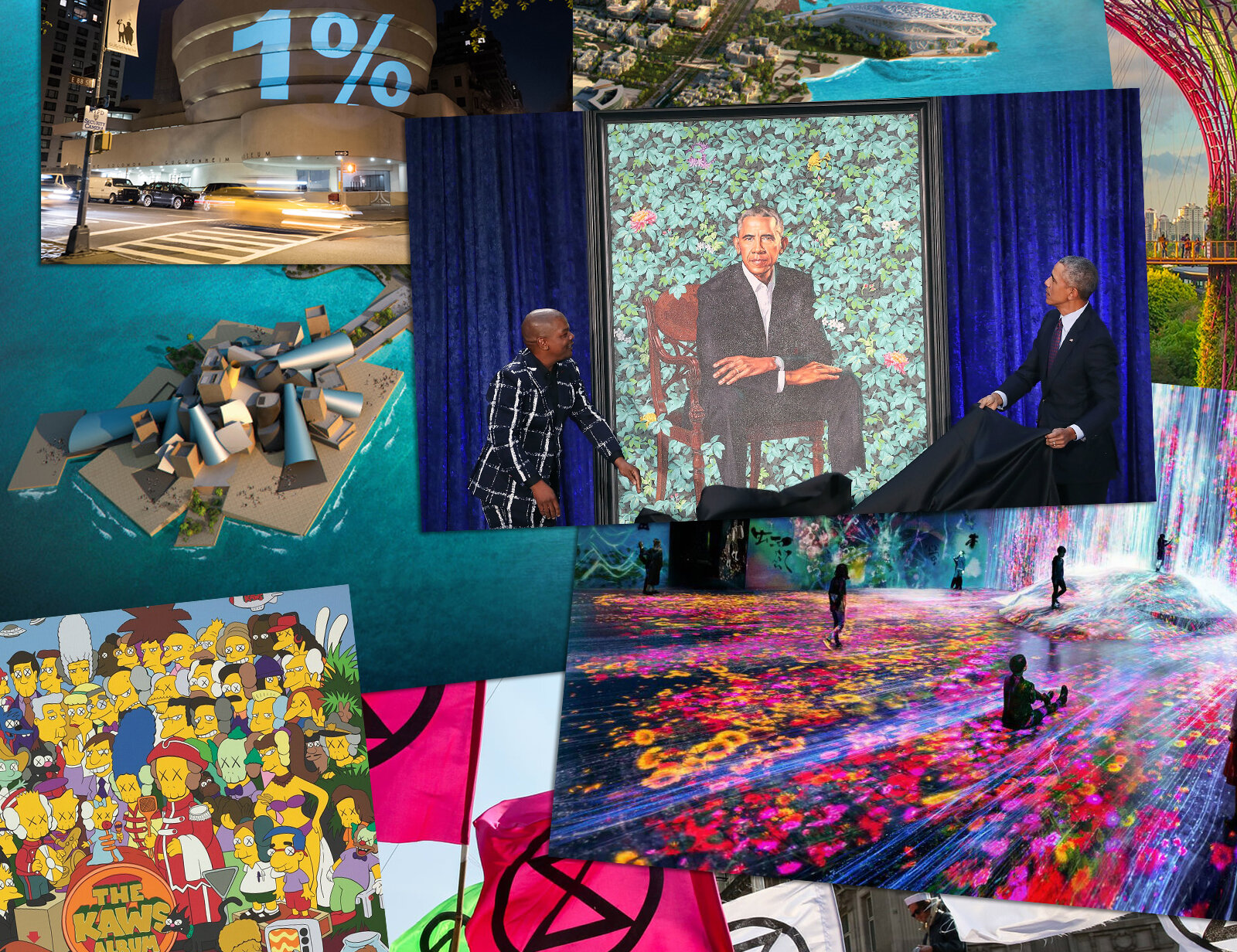

Rockwell painted a consistent positive vision of American life throughout the tumultuous 20th century, which included both World Wars, the Great Depression, and the Space Race. Rockwell also maintained his style of painterly realism during the era of modern art — an unusual feat — amidst the rebellion against tradition. “Norman Rockwell was demonized by a generation of critics who not only saw him as an enemy of modern art, but of all art,” notes Deborah Solomon, author of the Rockwell biography American Mirror.

The cover art for Norman Fucking Rockwell! (photographed by Del Rey’s sister, Caroline “Chuck” Grant) does not appear to be visually inspired by the titular artist. Instead, the most obvious aesthetic homage is dedicated to Rockwell’s contemporary — and fellow Arts Students League graduate — pop artist Roy Lichtenstein in the form of a comic book explosion.

Pop art was a response to the years following World War II, characterized by economic growth, mass production, standardization, and consumerism. In 1964, art critic Brian O’Doherty wrote that pop art was a nihilistic response to the “neutrality of emotion and this annihilation of the self” that is best expressed by leading pop artist Andy Warhol who himself once said, “I wish I were a machine.”

Thomas Kinkade — a contemporary artist who rejected modern art — argued that he, much like Rockwell, fought the “ugliness and nihilism of modern art and its irrelevance to his own life-affirming populism.” Through the juxtaposition of Lichtenstein and Rockwell, Del Rey embraces the idea “that it’s okay for the culture to be in a bit of disruption” because turmoil is a natural part of life.

In the album’s final track — dedicated to postwar American poet Sylvia Plath who ultimately committed suicide in 1963 — Del Rey proclaims, “Hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have but I have it.” With Norman Fucking Rockwell! Lana Del Rey seeks a return to the sentimental, the human, and the hopeful. Will she succeed? Will America?