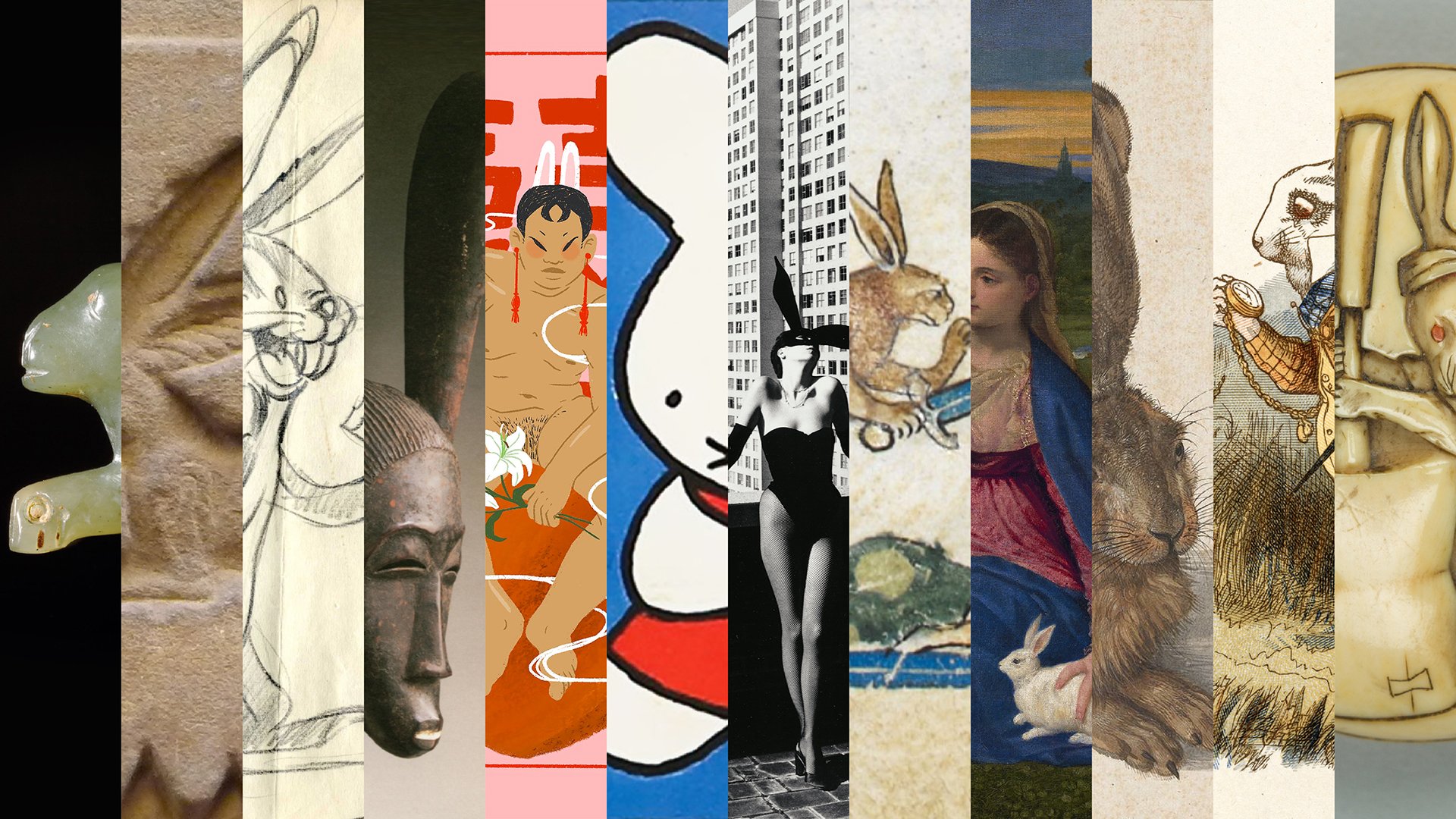

Accident of History, Valentine's Day

A brief history of the bizarre tradition.

Cover photo: Must I Confess?, card, by the Obpacher Brothers (1884). Via the Library of Congress (cropped).

Strange Origins

An extravagant day of love, Valentine’s Day is often denounced as a mere Hallmark Holiday but its origins are far more complicated.

The late journalist Alexander Chancellor summarized, “Valentine’s Day is a creation of the sentimental Victorian era and based on the flimsiest of traditions, rooted in an obscure reference by Chaucer to the saint’s day of an obscure early martyr who had no known interest in love or romance”. And yet the annual event endures.

The Real Valentine

Valentine’s Day was preceded by the pagan holiday of Lupercalia, a festival of purification celebrated with nudity and animal sacrifice. Women would be whipped with the bloody hides of slaughtered goats to ward off pestilence and infertility. (February is derived from the Latin word februare, meaning “to purify.”) Horrified by the practice, the fifth century Pope Gelasius chose the feast day of a Saint Valentine to compete with the event.

As many as 30 Saint Valentines are believed to exist, but the one Gelasius chose was a third-century Roman bishop, martyred on February 14th.

The Bollandists, an order of Belgian Jesuits who maintain archives on the lives of saints, have not found any historical basis for these legends. In 1969, the Roman Catholic Church ultimately removed Saint Valentine from the General Roman Calendar due to a lack of reliable information.

Chaucer’s Lovebirds

In fact, Geoffrey Chaucer — of The Canterbury Tales fame — is credited with creating the foundation for the modern Valentine’s Day in the late 14th century with Parlement of Foules.

In the 699-line poem, Chaucer satirizes courtship through a dream-vision of a gathering of birds. Three eagles vie for the attention of a female, and a variety of species offer advice.

The story is thought to be inspired by the 1382 marriage of Anne of Bohemia and avian enthusiast King Richard II. Nature personified coordinates the annual event, which Chaucer sets on Saint Valentine’s feast day.

For this was on Saint Valentines day,

Whan every brid cometh ther to chese his make,

Chaucer brands the occasion as a celebration of love and life, marking the end of dark winter nights, establishing the association of nature, spring, and lovebirds, with romance.

Saint Valentin, that art ful heigh on lofte,

Thus singen smale fowles for thy sake:

Now welcome, somer, with thy sonne softe,

That hast thise wintres wedres overshake,

And driven away the large nightes blake.

He also mentions both Venus and Cupid in the poem, the latter of which has become an iconic part of Valentine’s Day imagery.

I wol nat serve Venus ne Cupide Forsoothe,

as yit, by no manere waye.

Through the tale, notes Jean E. Jost, Professor of English at Bradley University, Chaucer interrogates ideas of “hierarchy, power, and gender.” The female eagle maintains her agency and right of refusal; she decides to postpone her choice for the following year.

Chaucer’s vision of Valentine’s Day quickly spread. In 1400, under the name Cour Amoureuse, a group of French lords organized a love-poem competition to be presented to, and judged by, Parisian ladies.

President of the National Valentine Collectors Association, Nancy Rosin writes for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “The popular holiday was embraced and celebrated across all strata of society with parties, balls, and the quintessential elaborate paper greetings that became a veritable hallmark of British and American Victorian life.”

Money & Marriage

In the 19th century, explains journalist Keyonna Summers, Valentine’s Day was particularly important in that it allowed couples to negotiate “that complicated relationship between romantic love and the economic reality of marriage.”

In her 1882 book Gems of Deportment and Hints of Etiquette, American journalist Martha Louise Rayne observed, “Love is very delightful, of course; but when it is fortified by a generous bank account [girls] are more favorable to its approaches.”

In Britain, just 25% of women worked, mostly young singles from poor families. It was important to find a husband who could provide financial security. Valentine’s Day proved to be a crucial test before marriage.

Typically, women would marry in their early twenties, to a man five years older. “The older the groom, the higher up the social scale he is likely to have been,” writes historian Ruth A. Symes in her 2015 book Family First: Tracing Relationships in the Past.

Cards & Consumerism

Throughout history, letters were a vital aspect of courtship. Sent as early as 1667, Valentine’s cards were originally handwritten, popular even prior to the invention of postage stamps in 1840. In London, an estimated 200,000 Valentine’s cards were sent annually throughout the 1820s, a number which quadrupled by the 1860s.

Still, there was a veritable Valentine industry. Suitors could purchase Valentine’s Manuals, featuring artwork and verses to serve as inspiration. Featured motifs included springtime, birds, and flowers. Rhymes were also popular.

Handmade cards fell out of favor by the 1850s, due to the rise of industrial manufacturing. Advances in printing techniques were impossible to resist. These cards boasted rich colors, embossment, and appliqué, as well as die-cuts and silk fringe.

Jewelers, florists, and confectioners were eager to join in the annual celebration. Sweethearts conversation hearts date back to 1902, the creation of two brothers in Boston, Massachusetts. Today, Americans celebrating Valentine’s Day expect to spend an average of approximately $175 for the occasion.

Hallmark was established in 1910. With extensive marketing, the company popularized the exchanging of Valentine’s cards in elementary schools. Today, it’s the largest greeting-card manufacturer in the world.

The continued success of Valentine’s Day can be attributed to the act of prosocial spending on which it is dependent. Prosocial spending — spending money on others — is found to make consumers happier than spending on themselves, which is good for lovers and businesses alike.

White Day

In Japan, Valentine’s Day is one of two special gift-giving days. On February 14th, only women are expected to give gifts — usually chocolates — to lovers, friends, family members, work colleagues, and bosses.

A month later on White Day, March 14th, men reciprocate with gifts double or even triple the value of their Valentine presents. The day was started by confectionary shop Ishimura Manseido in 1978. Named after the color of purity, traditional White Day gifts include marshmallows, gloves, stationary, and jewelry.