The Homoerotic Horrors of Alexander Glass

Interdisciplinary artist Alexander Glass is working in the intersection of horror and homoerotica to understand the male body through fear and desire.

Cover photo: Detail from Head in the Game, multi-media installation, by Alexander Glass (2016). Via the artist’s website.

WARNING: The following article features and/or discusses homophobia, homoerotica, AIDS, nudity, objectification, and eating disorders.

Alexander Glass

British sculptor and installation artist, Alexander Glass works in the intersection of horror and homoerotica. Glass proclaims, “My work is a discussion of masculinity and its complicated relationship to desire.” He is a multidisciplinary artist that creates work around testosterone filled spaces like swimming pools, showers, gyms, and locker rooms.

Glass focuses on the objectification of male bodies, specifically in athletic environments in which cinema has traditionally fetishized both the male physique and men’s homosocial relationships. In Glass’ senior thesis, Homo-erotica & Horror: thematic potentials of sports spaces, he examines “why these spaces are so often used as legitimizing scenarios of both male objectification and violence.”

In Glass’ senior thesis, he writes, “The sports space has been used as a visual device for legitimately eroticising the male athletic body, presenting it as a potentially passive image, to be merely observed. This in itself, to some, is a horror.”

Glass writes, “The fact that Olympic sport was a man’s activity for the spectacle of men sustains that it was both a homo-social and homoerotic activity.” Referring to gymnasiums, Glass adds, “This leaves the modern representation of the space in a state of ironic ignorance.”

In this vein, Glass’ interest with athleticism is reminiscent of fellow British artist Eddie Peake. However, unlike Peake, Glass investigates the queer awkwardness and fear associated with these spaces.

Fear vs Desire

Locker rooms are places for both voyeurism and exhibitionism, where men examine and judge each other. For curious males, these spaces present a forbidden desire. The vulnerable intimacy of a locker room is also a place for simultaneous homoerotica and homophobia, where nude men snap other with towels while denouncing any homosexual attraction.

About his interest in swimming pools, showers, gyms, and locker rooms, Glass explains, “There are two main parts. One is the awkwardness I find in those spaces. I feel like growing up as a gay kid you see yourself looking at other bodies in those spaces and find it incredibly awkward. Also, in terms of my work, I wanted to re-imagine those scenarios, but there’s also a cinematic feeling I try to draw upon. In movies and cinema, you get those spaces made so beautiful, which historically I have found frustrating and awkward. It’s rich ground for me.”

Glass is inspired by the gay representation in movies like homoerotic thrillers by former porn-director David DeCoteau or A Nightmare on Elm Street 2, an allegory about a boy overtaken by homosexual urges.

“I had quite a horrific accident in a swimming pool when I was quite young where a school teacher sent me to get changed by myself and I slipped and hit my head on the edge of a tile,” Glass admits. This also explains the sterility of his installations and the increased sense of anxiety. Glass’ installations are mostly empty, and alienating.

Violence as Transformation

The primary function of a gym is the transformation of the body and mind. In cinema, there is a tendency to “displace eroticism around the male body with horrific violence” through, as describes Professor Yvonne Tasker, “ritualized scenes of conflict.”

Glass posits the gym serves as an extension of this conflict, allowing males (both heterosexual and homosexual) to find strength and temporary invincibility through self-inflicted pain. Glass writes, “Homosexuality and weakness have been historically characterised as linked and the gym offers a space to dissolve this conception.”

According to Statista, the number of memberships at fitness centers and health clubs in the United States has trended upwards for the past couple decades, nearly doubling since the year 2000. Similar trends can be seen in Britain.

US Health and Fitness Memberships

Glass notes gym membership increase has coincided with a rise of men diagnosed with eating disorders. The British National Health Service reported in 2017 that the number of adult men admitted to hospitals with eating disorders had risen by 70% over the previous six years. Steroid use has increased as well.

Idealized body standards — which long plagued women — featured in media, including movies, advertising, and pornography are now contributing to men’s own body dysmorphia.

“Pressure for body perfection is on the rise for men of all ages, which is a risk factor for developing an eating disorder. Images of unhealthy male body ideals in the media place unnecessary pressure on vulnerable people who strive for acceptance through the way they look,” explains Dr. William Rhys Jones of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ eating disorders faculty. It is estimated that 20% of gay males suffer from anorexia and 14% from bulimia.

Both professional male athletes and gay men are especially vulnerable to eating disorders. One study notes, “The issue of weight concerns among males often is influenced by athletic achievement. More men than women are motivated to lose weight, or sometimes to gain weight, to achieve optimal performance in sports, and even in some cases, to be eligible to compete.” A 2004 study revealed about a third of male athletes suffer from eating disorders (compared to two thirds of female athletes).

Gay males are particularly image-obsessed. Among men who have eating disorders, 42% identify as gay. Objectification theory posits that societal minorities feel greater pressure to achieve and maintain an idealized body. In a 2016 study, 32% of gay and bisexual men reported they have a negative body image.

Muscularity is conflated with masculinity; especially for gay males, defined muscles serve as a defense against accusations of — the equally conflated — weakness and femininity. During and after the AIDS crisis, there was a reinvigorated interest in gay men to exercise in order to avoid looking frail or diseased, which Dr. Murray Drummond calls “protest muscularity.”

Today, however, the desire for muscularity is related to conforming to societal norms. “Given the rise in popularity of Instagram, influencers and celebrity culture, there has been a dramatic shift in the body ideals of men across the board; now both straight and gay men feel pressured to live up to this — I most definitely do,” admits one anonymous gay man.

There are no easy solutions to these problems. It is important to understand that a perfect body, even if attainable, will not guarantee happiness or feelings of self-fulfillment. Less exposure to unattainable body ideals in media is also recommended.

Judging others less harshly will help to judge oneself less harshly as well. The value of a human being should not be judged by their physical body. If you have developed an eating disorder, speak to a doctor or therapist.

Sexualization

Glass’ work raises concerns about the idealized male body through a queer gaze. Glass explains, “The ‘gaze’ in my research, and that is suggested in my installations, is always a sexual male gaze on arenas of the masculine. I think through this I give myself a power within my art to sexualize the heterosexual male body in a way that is much harder to do within everyday life.”

In the absence of sexual queer role models, gay males are left to lust for straight men. Glass realizes, “It’s always been that for me. It could be one of those internalised homophobia things, but that’s the sexual role model that has been sold to me. Your typical heartthrobs have been mostly heterosexual, but then you can use that stereotype and play it back.”

Still, Glass doesn’t seek to sexualize straight men in his work. The few representations of the male body in his installations are that of Glass himself. Glass explains, “There have been a few actors that have said in the past that the only way to combat the sexualisation of women is to sexualise men more. That’s not really the case and I don’t really believe that. The conversation about female bodies has usually been about how it’s done by the male gaze, the male director for example. When it comes to the sexualisation men, people tend not to see it as a problem, which I’m not sure is or isn’t as it should be. People don’t want to admit to it. On sexualisation generally, it’s not always bad but it’s more the implications that come with it.”

The conversation revolving sexualization, objectification, and power is complicated. Just this year, gay beauty influencer James Charles was accused of attempting to coerce straight men into sexual encounters.

While queer men may feel some kind of excitement or liberation in desiring straight idealized men, this does not excuse predatory practices. Gay photographer Matt Lambert, argues that straight men should not be subject to objectification by queer men in positions of power.

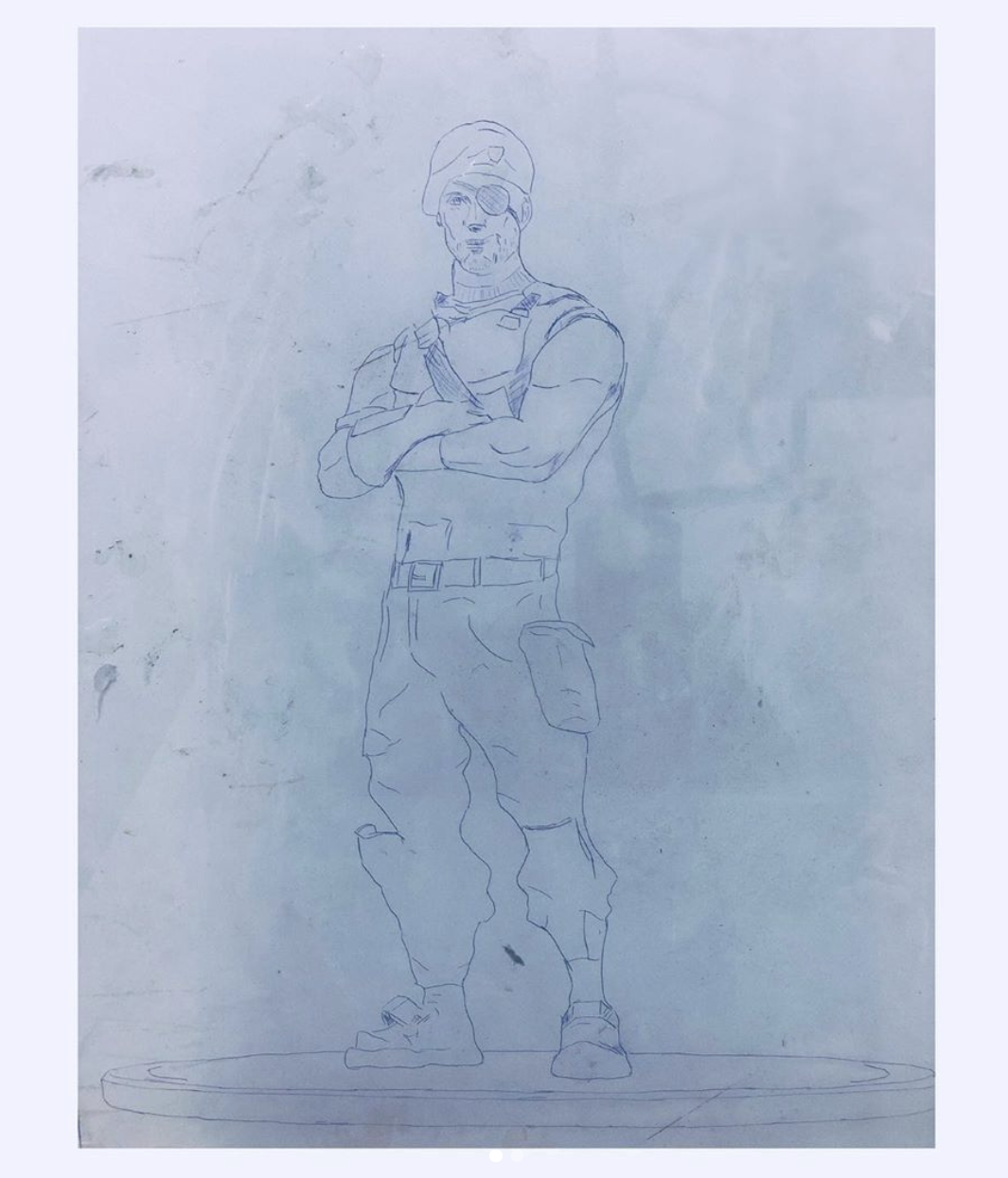

Superheroes and Gaming

Glass recently wrote an article about The Future of Gaming for Dazed. Similarly, his upcoming projects are going to tackle the idealized subject of superheroes. “I think the X-Men are an interesting foundation for me because I loved them as a kid, loved them as a teenager and love them now,” Glass explains. The X-Men comics are thought to be an allegory for gay rights, with the subtext of mutants embracing their differences.

Undeniably, all comics feature an idealized version of masculinity through the male body (Captain America’s muscular transformation immediately comes to mind). French artist duo Pierre et Gilles completed their series Heroes in 2014, and I’m curious to see how Glass’ work will differ conceptually. In the meantime, follow Glass on Instagram.