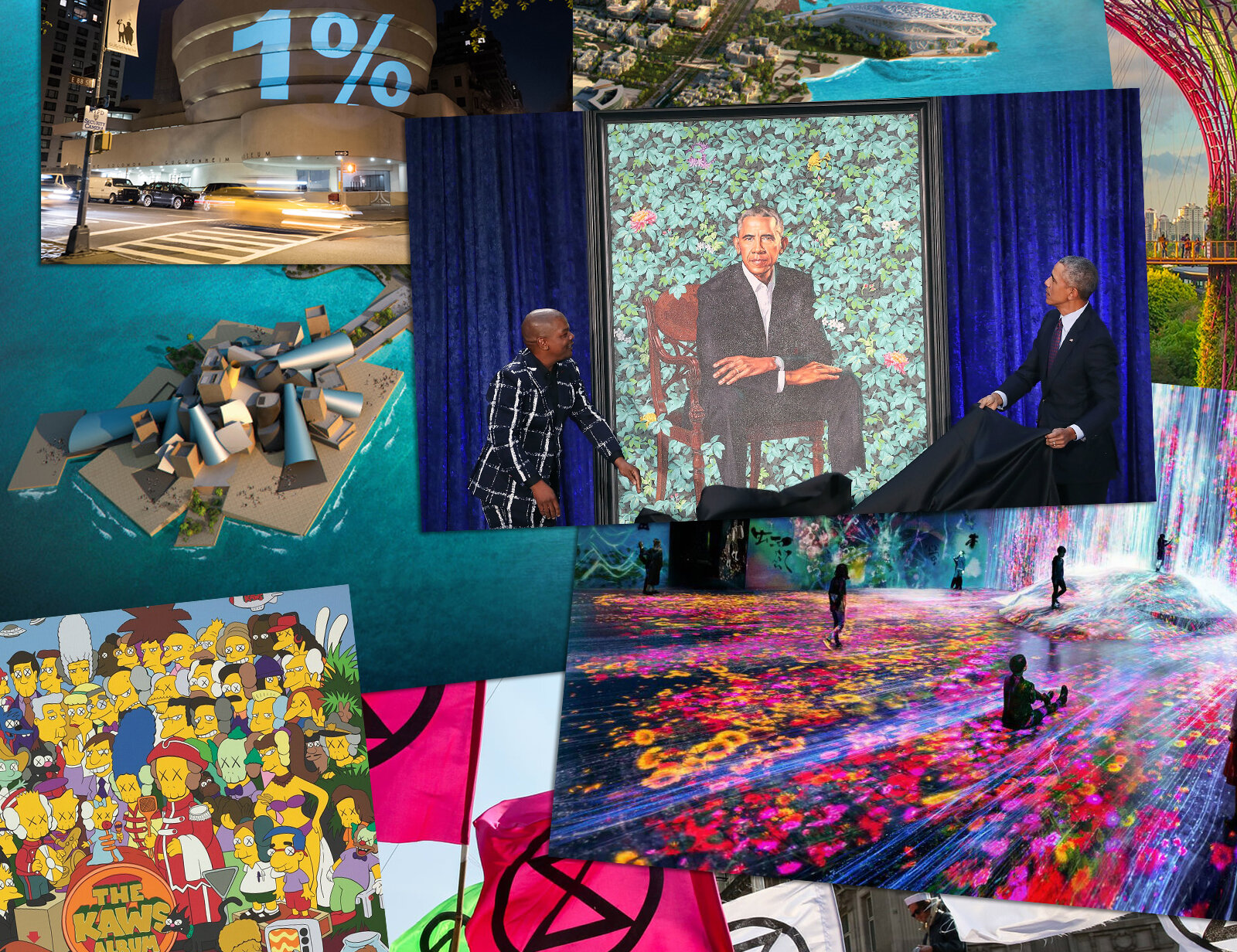

Remembering Painter Chuck Close

The acclaimed portrait artist Chuck Close has died at the age of 81.

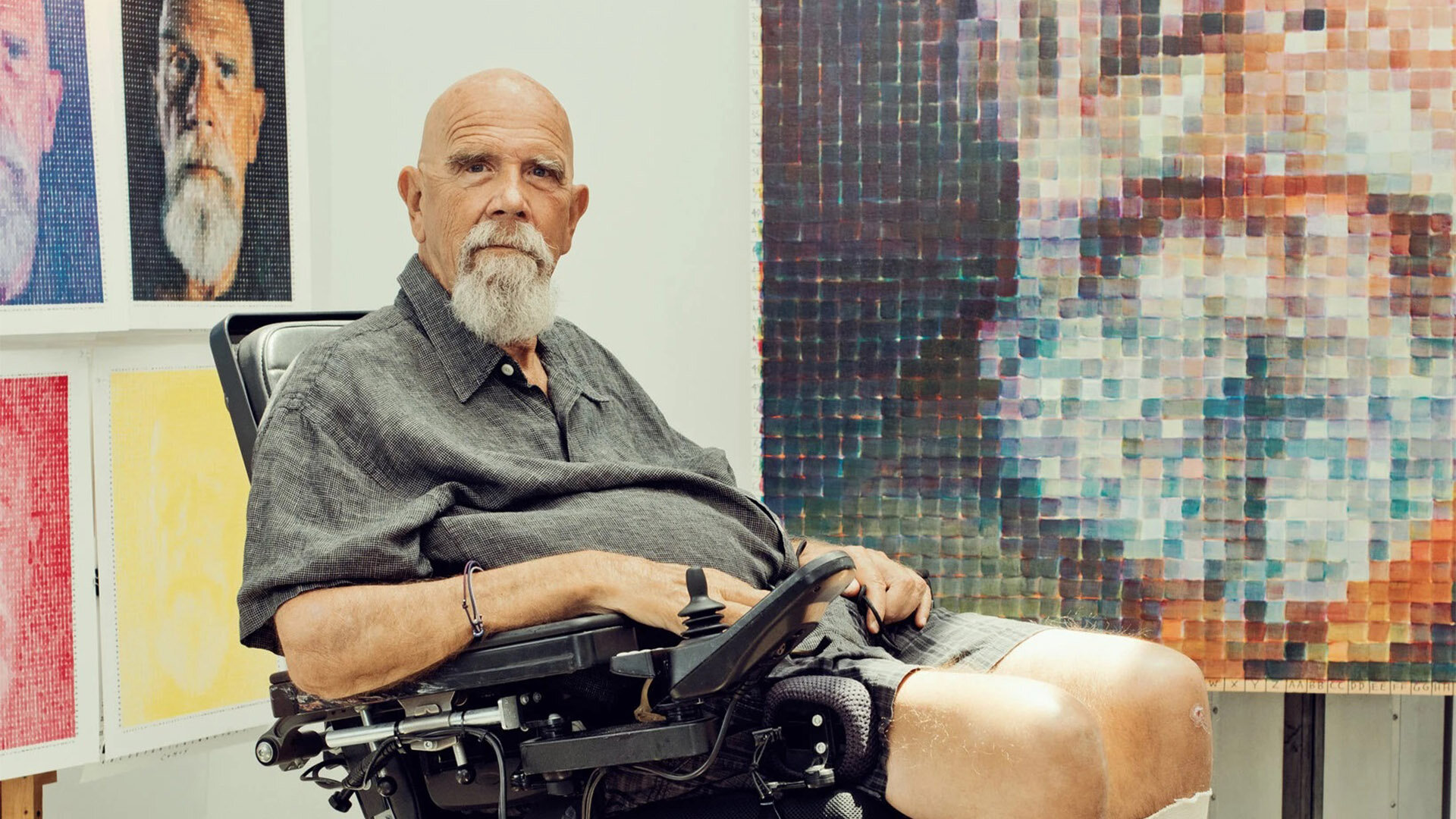

Cover photo: Chuck Close at his home in Long Beach, New York, United States (2017). Photo by Ryan Pfluger for The New York Times.

Close rose to prominence in the 1970s for his larger-than-life photorealistic portraits. He employed a grid system that allowed him to faithfully reproduce images from polaroid photographs.

Close was a master of color, tint, and shade. It was his conditions of dyslexia and prosopagnosia which spurred his interest in art. Close explained, “I was driven to make portraits because I have face blindness, and I want to commit images to memory of people that I know and love.”

Close found success thanks to — not despite — his neurological conditions. As he stated in his own words, “Almost every decision I’ve made as an artist is an outcome of my particular learning disorders. I’m overwhelmed by the whole. How do you make a big head? How do you make a nose? I’m not sure! But by breaking the image down into small units, I make each decision into a bite-size decision. I don’t have to reinvent the wheel every day. It’s an ongoing process. The system liberates and allows for intuition. And, eventually I have a painting.”

Close’s tenacity and perseverance was an inspiration. He continued making work after a spinal artery collapse left him paralyzed at nearly 50 years old. According to the BBC, Close told friends, “I’ll spit on the canvas if I have to.” His studio was equipped with a motorized easel that allowed him to lift, lower, and rotate his canvas.

The end of Close’s career was marred by scandal, as — during the height of the #MeToo movement — multiple women who had posed for the artist accused Close of sexual-harassment. Close apologized but maintained he had done nothing wrong. The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., indefinitely postposed an exhibition of his work.

Close had been diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia in 2015, which his neurologist, Dr. Thomas Wisniewski, credits for any possible “[s]exual inappropriateness”.

While Close’s personal life reignited discussions about separating art from artist, he leaves an indelible legacy.