Mona Lisa in the 21st Century

Should we still care about the world’s most famous painting?

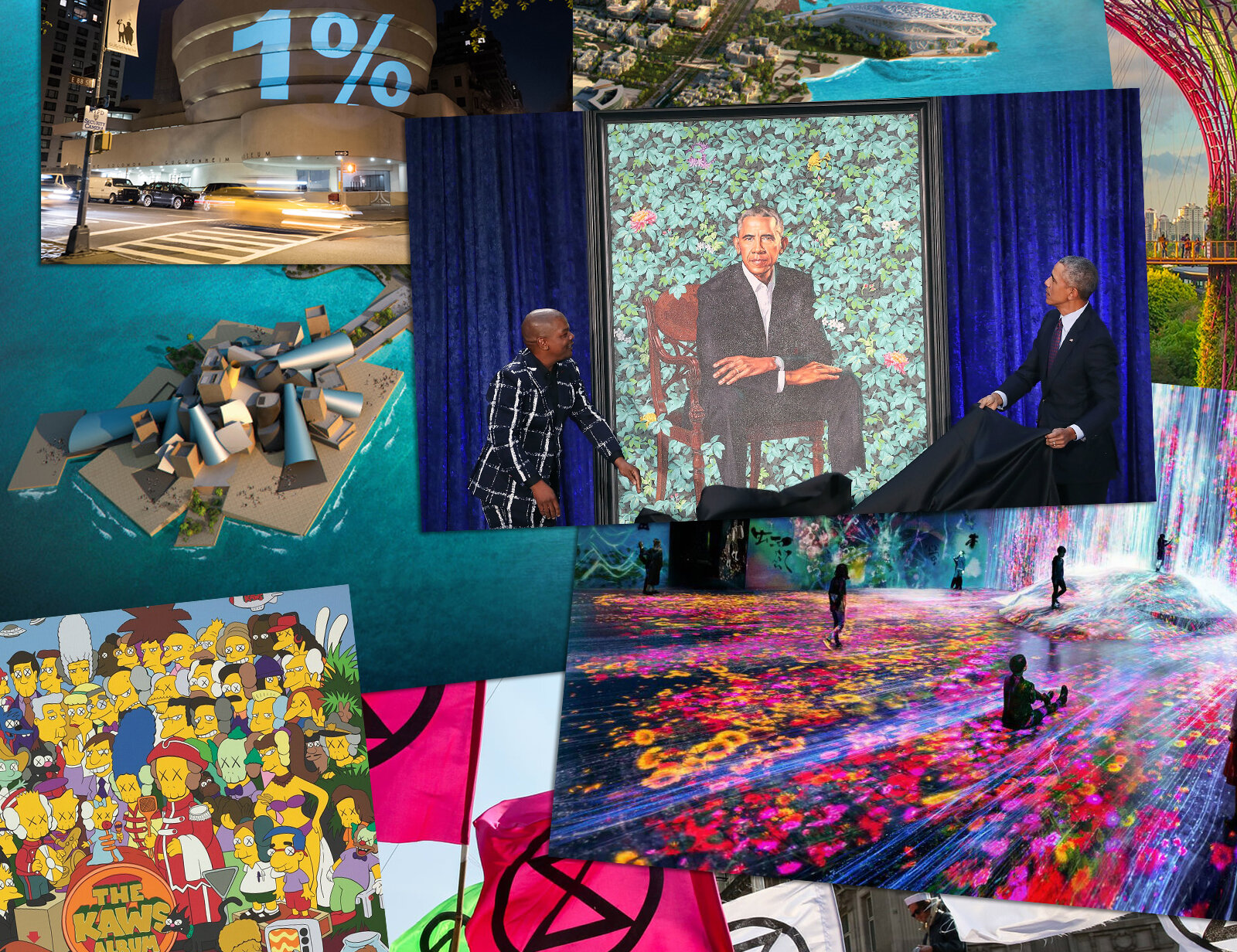

Cover photo: Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa is engulfed by flames in the mystery film Glass Onion, directed by Rian Johnson (2022). Via Netflix.

WARNING: This article contains spoilers for the film Glass Onion.

Intro

In his mystery film Glass Onion (2022), director Rian Johnson offers a provocative visual, Leonardo da Vinci’s iconic Mona Lisa set ablaze. The climactic scene is a framed as moment of catharsis, the triumph of a working-class teacher over a murderous tech-lord. Johnson provokes many questions: Why do we still care about this obscure Florentine aristocrat? What does the world’s most famous and valuable artwork represent today?

Glass Onion

The murder-mystery genre offers a unique opportunity for socio-political commentary, interrogating themes of wealth, class, and power, in search of motives and suspects.

In the follow-up to Knives Out, private investigator Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig) returns for another mystery with a new cast of characters, centered around the tech billionaire Miles Bron (Edward Norton), a thinly-veiled parody of real-life celebrity-businessman Elon Musk.

Bron invites his friends and fellow “disruptors” to party at his island getaway, including former business partner Andi Brand (Janelle Monáe), revealed to be her twin-sister Helen seeking revenge for her murder.

COVID-19 proves to be a crucial plot-device, necessary for a momentary suspension-of-disbelief when Bron explains the Government of France agreed to loan out the world’s most valuable painting due to financial pressures caused by the pandemic.

Prior to COVID-19, the Louvre welcomed an average seven million visitors annually. While the museum did close to the public March through July of 2020, the Mona Lisa is unofficially considered immovable due to the painting’s fragile condition and economic impact.

Louvre Attendance Over the Last Century (millions)

It’s unimaginable but technically possible for the painting to be sold. According to Article 451-5 of France’s Heritage Code, all objects held in the national collection are considered important cultural heritage and thus inalienable public property, however there is an established process for deaccession.

Formed in 2010, the Commission Scientifique Nationale des Collections (National Scientific Commission on Collections) would have to approve any public institution’s request for declassification and removal of an item in their possession, though this is unlikely except in extreme cases such as repatriation.

In May of 2020, one of France’s own tech-entrepreneurs, Stephane Distinguin, founder of the IT company Fabernovel, proposed the state should sell the Mona Lisa — for “no less than €50 billion” (approx. 54 billion USD) — to pay off mounting government debt, though it would be a mere drop in France’s total €3 trillion (approx. 3.3 trillion USD), the third-largest government debt in the world, after the United States and Japan.

“An obvious reflex [to the pandemic crisis] is to sell off a valuable asset at the highest price possible, but one that is the least critical as possible to our future,” argued Distinguin, seemingly unaware the Mona Lisa adds an estimated €3 billion (3.3 billion USD) to the French economy annually, meaning she would generate the €50 billion sum in just under 17 years.

According to a leaked 2018 report for the French Ministry of Culture, 90% of visitors come to the Louvre for Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, and removal of the painting would result in a staggering loss of 228,000 euros (approx. 240,000 USD) per day for museum facilities alone.

For Bron, Mona Lisa is a symbol of legacy. He reminds his guests, “I want to be responsible for something that gets mentioned in the same breath as the Mona Lisa, forever.” Obsessed with the painting, Bron has chosen to disable the Mona Lisa’s glass protection to better appreciate the work, housed in his Grecian mansion, powered by Klear, his new and untested biofuel.

As foreshadowed by her demolition of the puzzle-box invitation, Brand destroys multiple glass sculptures, before finally incinerating the Mona Lisa; thus Bron has his life’s dream fulfilled, to be forever associated with the painting, but as the man responsible for her destruction.

Glass Onion is a klear condemnation of Silicon Valley’s disruption culture, exemplified by Facebook co-founder Mark Zuckerberg’s motto, “Move fast and break things.” Blessed with ego and unburdened by a sense of social responsibility, this entrepreneurial mindset rejects regulation, tradition, and established best practices in the name of speed and innovation.

Silicon Valley’s practices of tax-avoidance, wage suppression, and censorship have had far-reaching effects on communication, economy, and democracy worldwide. Director Johnson explains, “I’m always creatively driven to put what I’m angry about at the moment into movies.”

Both Glass Onion and Knives Out are deeply humanist, placing morality and empathy before rigid legality. As a private investigator, Blanc is able to operate outside the law, governed instead by his own sense of ethics.

The heroines of both films are imbued with a sense of righteousness. Marta Cabrera is physiologically unable to lie, owing to a medical condition which makes her vomit. About Helen Brand, Emily Kavanagh writes for Collider, “we know she’s doing what needs to be done, breaking what needs to be broken to finally set things right.”

Glass Onion concludes with Brand facing the camera, mimicking the painting she has destroyed to avenge her murdered sister. The film argues that humanity is worth more than the most famous object in the world. Says Johnson, “she burned the Mona Lisa but the Mona Lisa lives on in Helen.”

Leonardo as Disruptor

Considered one of the most talented people in history — the original Renaissance man — polymath Leonardo da Vinci could certainly be labeled a disruptor. In fact, he is something of an idol among entrepreneurs, who excitedly compare 15th century Florence to California’s Silicon Valley.

“Just as innovation changed the world during the Renaissance, innovators in technology are changing the world today,” argues Polish-American painter Agnieszka Pilat, a self-described “technology romantic.”

Microsoft co-founder, Bill Gates, reveals, “I’ve been fascinated by the artist and inventor Leonardo da Vinci for decades. He had one of the most innovative minds ever.” Upon the Apple co-founder’s passing, Softbank CEO Masayoshi Son (孫 正義) declared that Steve Jobs “will be remembered alongside Leonardo da Vinci.”

“[Leonardo] had the ability to make connections that we did not know existed. He was able to see patterns across disciplines,” lauds biographer Walter Isaacson. Leonardo was born an outsider. As the illegitimate son of a notary and a peasant girl, he was free to follow creative pursuits, developing an inexhaustible curiosity, studying zoology, botany, geology, geometry, mathematics, optics, machinery, aerodynamics, and engineering.

In opposition to the Catholic Church, he secretly dissected corpses to better understand the human body, pioneering the field of anatomy. The Black Plaque had decimated Europe in the 14th century, killing over a third of the continent’s population. The Church had suffered a crisis of confidence; the masses searched history for answers.

The Renaissance (literally “Rebirth”) witnessed a rediscovery of the classical world, exemplified by Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man, based on the theories of 5th century Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio. In a fusion of art and math, Leonardo illustrates the perfect design of man, in harmony with — and in ultimate representation of — the entire cosmos.

Rooted in studia humanitatis (the studies of humanity) — specifically grammar, rhetoric, poetry, history, and moral philosophy — the prevailing intellectual movement of humanism elevated the value and dignity of the individual, promoting personal education, autonomy, and civic engagement.

Humanism proved compatible with a variety of beliefs. Leonardo himself accepted God, creating several religious works for patrons, including The Last Supper (L’Utima Cena) for a Dominican convent in Milan.

As a resident artist at the robotics firm Boston Dynamics, Pilat’s rendition of Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man features the company’s humanoid robot Atlas. Meeting the machine, Pilat says, “was a really spiritual experience for me.”

Leonardo himself is credited with designing the first automaton, but unlike MVP (Minimum Viable Product) tech creators, Leonardo was a terrible perfectionist, leaving behind few completed projects and just 15 authenticated paintings.

The Renaissance Portrait

Art historians largely credit Renaissance Florence with the reemergence of the domestic portrait genre. European portraiture had “essentially disappeared” with the collapse of the Roman Empire.

Prior to the 15th century, explains art critic Ken Johnson, “Portraits were for kings, popes, saints and other luminaries … and their images were meant for official, more or less public display at sites like churches and tombs.”

Due to the influence of the Medici banking family, Florence (Firenze) became the center of European trade and finance. The growth and diversification of societal roles created a new group of patrons who desired their own portraits to commemorate their individual identities.

Florence was a site of artistic innovation, because “artisans” were driven by “the need to be industrious … [and] to know how to make a living, [and] competition … is one of the nourishments that maintain them,” wrote Vasari, one of history’s first authors to use the word “competition” (concorrenza) in an economic sense.

“Humanism became very important, so the self did too,” explains Matthias Ubl, curator at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. “The growth of cities saw the rise of a mercantile elite which wanted to mirror the nobility by having their portrait painted.” In short, independent portraiture evolved both as “a symptom of expanding consciousness of the self” and as an “[economic] response to a demand,” writes art historian Rab Hatfield.

Inspired by the rulers found on ancient Roman coins, Florentine Quattrocento (1400s) portraiture first featured sitters in idealized profile. These portraits reflected trends in beauty, including slender necks, thin eyebrows, high hairlines, and ostentatious jewelry.

According to Le Gallerie Degli Uffizi (The Uffizi Galleries) in Florence, this style “guaranteed a remarkable likelihood and precision in the rendering of details,” as can be seen in the portrait of Battista Sforza, the Duchess of Urbino, by master painter Piero della Francesca. With its averted gaze, this severe angle was dignified, allowing for little emotion.

By the mid-century, Florentine painters began to depart from the Quattrocento profile. Motivated by competition — both in terms of reputation and economics — artists deviated from the classic style. Experimentation shifted portraiture from a focus on idealized appearance and symbols of status to likeness and personality instead.

While it was Florence that truly birthed the portrait genre, the development of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa can be traced back to Bruges, in the Netherlands, home to master artists like Jan van Eyck and German-born Hans Memling. Bruges was Northern Europe’s center of commerce.

“Van Eyck is … the most powerful painter in the western hemisphere. It is not Leonardo da Vinci. It is nobody else but Van Eyck,” argues contemporary Belgian artist, Luc Tuymans. A pioneer of oil painting and realism, Van Eyck was one of the first artists to create a body of secular portraiture, and the very first to create a Renaissance portrait with a gaze turned to the viewer.

Memling too was “a leading innovator in portraiture,” who perfected realistic detail, landscape backgrounds, atmospheric perspective, as well as the three-quarter pose. Arts writer Roderick Conway Morris notes, “more of his works found their way to Italy than those of any other Flemish painter.”

The earliest surviving example of three-quarter view by a Florentine artist is Andrea del Castagno’s Portrait of a Man, painted around 1450. However, unlike men, women remained confined by the idealized profile for another two decades, ultimately freed by Sandro Botticelli and Leonardo.

Born in 1452, young Leonardo moved to Florence in 1469, where he joined the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio, one of countless Tuscan artists including Filippo Lippi and Sandro Botticelli who were “responsive to northern art.”

Created nearly a quarter-century after Andrea del Castagno’s Portrait of a Man, Leonardo’s portrayal of Ginevra de’ Benci is one of the first Italian depictions of a woman in three-quarter-view. Painted when Leonardo was around the age of 22, this portrait laid the groundwork for the Mona Lisa. Besides his obvious attention to nature, and the use of three-quarter-view pose, Leonardo made the daring choice for Ginevra’s eyes to stare forward.

Women of Quattrocento Florence were taught to avert their gaze, as proof of modesty and obedience. Still, Leonardo insisted Ginevra de’ Benci was a lady of virtue. Inspired by her name, he frames Ginevra with ginepro (juniper), a plant which symbolized chastity.

Other artists introduced the use of windows and columns as framing devices. In Memling’s Portrait of a Young Woman (Sibylla Sambetha), Sambetha’s hands touch the edge of the painting. In Lady with an Ermine, Leonardo introduces contrapposto (torsion), with mistress Cecilia Gallerani’s face and body twisted in opposing directions. The animal she clutches is in reference to her lover, Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan known as the White Ermine.

Finally, in 1503, Leonardo combines all these innovations to create the Mona Lisa: mimesis, naturalism, atmospheric perspective, architectural framing, contrapposto, and symbolism. This is the culmination of his life’s work.

Leonardo also adopts and alters the pose of clasped hands from Flemish portraiture. Lastly, he blesses Lady Lisa with the slightest hint of a smile, a virtually unprecedented addition in portraiture, justified by her title La Gioconda. It’s a smile which would enchant and haunt men for centuries.

Mona Lisa is credited with popularizing the use of three-quarter-view in portraiture. An apprentice in Leonardo’s workshop, Raffaello Sanzio (Raphael) revisited the pose multiple times. The combined influence of old Leonardo and young Raffaello established three-quarter-view as the standard.

The Painting

Leonardo began the Mona Lisa around 1503, at the age of fifty. It was 16th century biographer Giorgio Vasari who first identified the portrait’s subject as Lisa Gherardini, the third wife of wealthy Florentine silk merchant Francesco del Giocondo, and an overwhelming majority of historians agree the Louvre’s painting portrays her. Francesco was friends with Leonardo’s father.

Upon marriage to Francesco del Giocondo, Lisa was called La Gioconda. The name is rendered in French as La Joconde, while her English name is a variant of the Italian monna, a contraction of madonna (madam) or mia donna (my lady), both honorific titles for a noblewoman. The focal point of Leonardo’s painting, the enigmatic smile, is a simple visual pun inspired by onomastics. She is La Gioconda: Mona Lisa, The Happy Woman.

According to Vasari, Leonardo had spent four years on the painting, allowing the panel to languish after 1507, sparking the legend that Leonardo used the final twelve years of his life maniacally perfecting Lady Lisa’s lips.

Her trademark smile has provoked infinite ideas. “She must have had nasty teeth to smile so tightly,” joked Dutch-French painter Kees van Dongen. Perhaps she is guarding a secret pregnancy. Others claim the smile is drawn from Leonardo’s own mouth or modeled after his apprentice and lover Gian Giacomo Caprotti, whom Leonardo called Salaì (Little Devil). In the viral 2022 mockumentary Cunk on Earth, fictional journalist Philomena Cunk (Diane Morgan) asks, “Is she holding a balloon between her legs?”

In the 1525 estate inventory of Caprotti, the portrait was first recorded as “Quadro dicto la Joconda” at the price of 505 lire. Jack M. Greenstein, Professor and Chair of the Visual Arts Department at the University of California, argues the use of the word dicto (called) rather than de (of) is significant, suggesting la Joconda is not meant as a proper noun.

Derived from the Latin iocundus, the Italian words giocondo (masculine) and gioconda (feminine) — used both as names and adjectives — mean “joyful.” Therefore the above phrase translates as “A painting called The Happy Woman.”

In 1910, the famed Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud posited that the smile was influenced by Leonardo’s repressed psychosexual dreams: “For if the Gioconda’s smile called up in his mind the memory of his mother, it is easy to understand how it drove him at once to create a glorification of motherhood, and to give back to his mother the smile he had found in the noble lady.”

Born in 1479, Lisa del Giocondo was just 24 years old when she posed for Leonardo. Married by age 15 to a widower nearly twice her age, she had just given birth to her second child.

Leonardo’s painting is a half-length portrait, rendered in three-quarter perspective. Lady Lisa sits in contrapposto; her right side is turned back but she gently twists her upper body to face the viewer, imbuing her with dynamism and grace.

These changes reflected real-life advances in women’s autonomy. In this light, Mona Lisa can be read as a culmination of growing trends. Staring directly at the viewer, she is a feminist icon, portrayed not only as a wife, but as a woman. She bears a serene smile while her eyes gaze forward.

Unadorned with jewelry, Mona Lisa is dressed in a low-cut gown featuring geometric embroidery and flowing sleeves. A sumptuous garment is folded over her left shoulder, befitting the wife of a silk merchant.

Mona Lisa is seated in a wooden pozzetto (little well) chair in a loggia (roofed gallery), before a mountainous landscape with cloudless sky. The nature is unspoiled but for a romanesque arched bridge (likely modeled after Ponte Buriano in Arezzo) on the right of the panel. The composition is tight. Only the bases of the flanking columns are visible, connected by the stone balustrade of the balcony.

Closer inspection reveals a transparent veil covering her high forehead, containing her loose curls which extend past her shoulders, pointing to her delicate hands. Her right hand gently grips the wrist of her left, resting upon the rounded chair. Both the balustrade and chair are placed parallel within the panel’s composition, establishing a linear perspective which pulls the viewer into Lady Lisa’s gaze.

Lady Lisa’s appearance has prompted countless medical experts to speculate about her health, with a recent diagnosis of hypothyroidism, which could account for her round face, thinning hair, and weak smile. Despite a litany of posthumous diagnoses, Lady Lisa was considered quite beautiful in her time, inspiring the creation of Leonardo’s lustfully nude Monna Vanna, possibly at the behest of Giuliano de Medici in Rome.

The painting was rendered with sfumato — Italian for “vanished smoke” — a technique inspired by atmospheric perspective in which boundaries are blurred to become imperceptible. In Glass Onion, Bron erroneously states, “Da Vinci invented a technique for brushstrokes that leave no lines.” While no one mastered sfumato like Leonardo, it was first developed by Flemish Primitive painters, including Van Eyck and Memling.

The painting is in extremely fragile physical condition. Executed on a thin board of poplar, the wooden base has warped and the paint layers have suffered much cracking. The image has yellowed and darkened over 500 years of oxidization, resulting in the rich sepia tones and green-hued sky visible today, though complaints of muddied varnish were recorded as early as 1625.

The painting has proven a popular target for vandalism and protest, enduring both a stone projectile and acid attack in 1956. Since then, Mona Lisa has been encased in bulletproof glass. She was threatened with spray paint in 1974 because Japanese authorities had refused entry to disabled people in effort to keep crowds moving at her exhibition in Tokyo. In 2009, a Russian woman threw a teacup at the painting after she had been denied French citizenship.

After Leonardo (1500-1900)

Lisa del Giocondo passed away in 1542, having never received the commissioned portrait for which she modeled. Mona Lisa was found in Leonardo’s French studio upon his death. He had brought the painting with him to Amboise in 1516, relocating upon the invitation of King Francois (Francis) I.

It’s a mystery as to why the painting was one of the three Leonardo took with him. Why was this commissioned portrait never presented to its likeness or not simply left behind? Leonardo had abandoned greater projects than this, so he likely felt no guilt in disappointing his father’s friend.

The most tempting answer is that during the work’s prolonged execution, Leonardo had grown personally fond of the image, and as he labored over the painting, it transcended the identity of Lisa del Giocondo to become something truly sublime.

King Francois I obtained the work sometime after Leonardo’s passing in 1519. According to French legend — a fantasy repeated by Vasari — Leonardo died in the arms of the king, who did in fact keep Mona Lisa at a gallery in Fontainebleau, his favorite chateau, where it languished in obscurity until it was installed at the Louvre in 1797, following the palace’s reopening as a public museum thanks to the French Revolution. The royal collection was now the collective property of the nation’s people.

Upon his coronation, Emperor Napoléon I — himself of Italian descent — slept with the Mona Lisa in his bedroom in the nearby Tuileries Palace from 1800 until 1804, when she was reclaimed by the Louvre, moved into the Grande Galerie (Grand Gallery).

Initially, Mona Lisa was simply regarded as one of countless masterpieces in France’s impressive collection. As American art critic Charlie Finch noted, in Samuel F.B. Morse’s pedagogical representation of the Louvre’s Salon Carré, “the Mona Lisa, obscured in the bottom row, is as comical and simply drawn as a Loony Tunes cartoon.”

Around 1840, experts valued La Joconde at 90,000 francs, a considerable sum — you could buy an entire house for 50,000 — that seems quite modest compared to 150,000 for Leonardo’s own Virgin of the Rocks or 600,000 for Raffaello’s Holy Family.

It was the male gaze, not Lisa’s, which would lay the kindling for her eventual stardom. She became a siren for the Romantics, a literary elite who transformed her from “Florentine housewife into an enigmatic femme fatale.”

In 1855, the poet Théophile Gautier, described a “gaze promising unknown pleasures,” with a power to make men “timid like schoolboys in the presence of a duchess,” while the historian and critic Jules Michelet wrote, “This painting attracts me, revolts me, consumes me. I go to it in spite of myself, like a bird to a serpent.” In 1852, Mona Lisa had sent young French artist Luc Maspero into insanity. His suicide note read, “For years I have grappled desperately with her smile. I prefer to die.” It’s also reported that in 1910, one man shot himself in her presence.

British critic Walter Pater showered her with hyperbolic prose in his much-lauded 1873 book The Renaissance:

She is older than the rocks among which she sits; like the vampire she has been dead many times, and learned the secrets of the grave; and has been a diver in deep seas, and keeps their fallen day about her; and trafficked for strange webs with Eastern merchants; and, as Leda, was the mother of Helen of Troy; and as Saint Anne, the mother of Mary … sweeping together ten thousand experiences …

Both eternal and all-knowing, Mona Lisa was reinvented as a timeless goddess, but she didn’t attract global attention until she was stolen.

Infamous Theft

When the Mona Lisa was taken from the Musee du Louvre on Monday morning, August 21st, 1911, staff didn’t realize until devoted copyist Louis Beroud complained of her absence the following afternoon. The Washington Post erroneously reported the theft with an image of Leonardo’s Monna Vanna.

The museum closed for a week. When it reopened, writes journalist Simon Kuper, “queues formed outside for the first time ever. People were streaming in to see the empty space where Mona Lisa had hung.”

The Spanish artist Pablo Picasso was suspected, and French poet Guillaume Apollinaire was even arrested, but it was a former Louvre employee; Italian carpenter Vincenzo Peruggia — he had made Lady Lisa’s glass frame — who had simply walked out with the painting, small enough to fit under his cloak. Peruggia had initially hoped to steal Mantegna’s Mars and Venus but the painting’s size (ten times larger than the Mona Lisa) made it impossible.

Supposedly convinced that Napoléon had stolen Mona Lisa from Italy, Peruggia claimed he wanted to repatriate the work to his homeland — though he had also considered selling the painting to British art dealer Joseph Duveen. The forger Marquis Eduardo de Valfierno later claimed Peruggia was his accomplice with a plan to sell copies of the Mona Lisa in her absence, though such a scheme was never realized.

Peruggia kept the painting hidden in Paris for two years, during which time speculation ran rampant and the Mona Lisa achieved mythological status. “It was on the front page of every major newspaper,” noted Seymour Reit, author of The Day They Stole the Mona Lisa. This was the greatest advertising campaign an artwork ever enjoyed, generating an incalculable amount of free press. Some critics accused the Louvre of hiding the Mona Lisa for publicity.

“I fell in love with her,” Peruggia would later confess. In 1913, he brought the Mona Lisa to Florence, showing her to an antique dealer, ready to sell the painting to the Uffizi Galleries for 500,000 lire. Authorities were alerted and Peruggia was arrested. A court-appointed psychiatrist diagnosed him as “mentally deficient” and his lawyer argued no one had been hurt. Peruggia was given a lenient sentence of just one year and fifteen days, ultimately serving only seven months.

Upon recovery, Mona Lisa toured Italy as a superstar before her gracious return to the Louvre on January 4th, 1914. Greeted by over 100,000 people in her first two days back, she was welcomed as the most famous painting in the world.

The Meme of Mona

A common subject for appropriation, the Mona Lisa is “undoubtedly the world’s most reproduced picture,” says Atsushi Miura, an art historian at the University of Tokyo.

In 1863, Italian artist Cesare Maccari imagined Leonardo entertaining Lisa Gherardini with hired musicians — and what appears to be a leashed monkey — to maintain her shy smile, a tale originated by Vasari.

Copies of the Mona Lisa were made concurrently with her creation, over one hundred of which survive today. During the two years of her disappearance, reproductions were the only way to glimpse the missing painting. Paris police alone distributed 6,500 images of the stolen masterpiece.

Thanks to newspapers, writes Rochelle Gurstein for The New Republic, “People who ordinarily cared little for art were inundated both with countless images of the painting and tales of its many legends, the enigmatic smile always occupying center stage.” In October of 1911, the Swiss-French newspaper Le Matin, ran an anonymous submission reading, “Poor Joconde!... Not only are these reproductions no consolation for the loss of the original, but they aggravate the regret.”

Upon her triumphant return, advertisers employed the icon of Mona Lisa to sell their products to the consuming masses. By the 1960s, Paris was one of the most popular destinations of the burgeoning global tourism industry, with Mona Lisa welcoming international visitors.

“The problem is she has become so famous that we don’t really see her anymore,” laments Jean-Pierre Cuzin, a longtime curator at the Louvre. “Imprisoned by its reputation,” the Mona Lisa is more symbol than painting. She is the world’s first meme, the quintessential portrait, a universal format. Transcending her status as a mere individual, Mona Lisa has become synonymous with the medium of painting and even art itself.

About destroying the Mona Lisa in Glass Onion, director Johnson explains, “It’s a sacred cow, but it’s almost more famous for being famous. It’s so ridiculous that the audience will make the leap and get the joke. As opposed to burning a Bible, for instance, or a flag, you know — something that could actually be offensive.”

The Mona Lisa is inoffensive precisely because she’s universal. Spahic Omer, Associate Professor at the Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences, writes, “Mona Lisa is an ambassador for the dignity and humanity of all people.”

Artists reappropriate work to legitimize their own practice, to increase their fame, to pay homage to their influences, or to play with established meaning.

Art critic Blake Gopnik suggests that Leonardo himself was the first artist to appropriate Lady Lisa’s image by removing the painting from Florence, and divorcing the portrait from its model. “This choice was nothing short of revolutionary in a world where the vast majority of art was produced via a contracted commission, and where independent creation for creation’s sake was virtually unknown,” writes Victoria Coates, a senior fellow at The Heritage Foundation.

Many parodies are made in rejection of Lisa’s perceived authority, alternatively criticized as Western, bourgeois, or — most frequently — feminine.

In a letter to the Norwegian artist Ragnvald Blix, the American author and humorist Mark Twain admitted, “I have always had an aversion to Mona Lisa,” and in 1916, art historian Bernard Berenson complained of her “pervading air of hostile superiority.”

The earliest known parody of the Mona Lisa was created by Eugène Bataille, under the pseudonym Arthur Sapeck, a member of the local anti-establishment Les Arts incohérents (The Incoherent Arts). Founded by Jules Lévy, the group held regular exhibitions of “drawings made by people who don’t know how to draw.” In Sapeck’s irreverent depiction, a rebellious Lisa smokes from a clay pipe.

A predecessor to the Dada movement, Les Arts incohérents was an inspiration to Marcel Duchamp, who created the first of his L.H.O.O.Q. works in 1919, upon the 400th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci’s death. The letters are a homonym for “Elle a chaud au cul” — literally “She’s hot in the ass” — meaning “She’s horny.”

Duchamp renders Mona Lisa masculine by adding a moustache and goatee to the noblewoman. After creating his own mustachioed portrait, the Spanish artist Salvador Dalí, declared Duchamp’s alteration as “an attack on idealized femininity.”

Likewise, the anonymous British graffiti artist Banksy depicted Mona Lisa with a rocket launcher, rendering her smile more devious than pleasant, transforming her from an image of cultural prestige to militarized violence, as an apparent critique of ongoing Western intervention in the Middle East.

Several artists have recreated the Mona Lisa in their own signature styles, like the anonymous Florentine graffitist Blub in his ongoing L’arte sa Nuotare (Art Knows How to Swim) series, Colombian Fernando Botero in his inflated Boterismo, and American neo-expressionist Jean-Michel Basquiat, replete with reference to jazz musician Nat King Cole.

Arranged by First Lady Jackie Kennedy, the Mona Lisa traveled to the United States in the 1960s, exhibited in Washington D.C. and New York City.

This was a momentous diplomatic event, further enshrining the relationship between France and the United States. President John F. Kennedy declared Mona Lisa a symbol of shared commitment to “democracy and freedom.”

Nearly two million Americans visited the Mona Lisa on her tour, catching the attention of rising pop artist Andy Warhol. She was one of the first subjects employed in his silkscreens and he would revisit the woman repeatedly, holding her in a pantheon of celebrities including Elizabeth Taylor and Marilyn Monroe.

In Thirty are Better Than One, Warhol multiplies the figure to embody the consumerist ideal that quantity is better than quality. “It almost becomes like decorative wallpaper,” says José Diaz, chief curator at The Andy Warhol Museum.

La Gioconda was later flown to Tokyo and Moscow, in the Soviet Union. 1.5 million people visited her in Japan, which remains a record exhibition attendance in the nation to this day.

The Mona Lisa had become exceptionally popular in Japan following the empire’s reopening in the 19th century, a symbol of the alluring, once-forbidden West. Meiji-era painter Kanzan Shimomura (下村 観山) modeled his Gyoran Kannon (The Goddess of Mercy) after Mona Lisa herself. Artists Yasumasa Morimura (森村 泰昌), Miran Fukuda (福田 美蘭), and Madsaki would each create their own images as well.

In 2008, the Louvre commissioned French-Chinese portrait artist Yan Pei-Ming (严培明) to create a series of paintings for the museum. “As soon as I received the invitation from the Louvre, I immediately thought of the Mona Lisa,” Pei-Ming explained. Washed in grey, his Mona Lisa Funeral asserts the immortality of the icon. “To bury the myth in order to revitalize the act of painting. This is a celebration and not only a funeral.”

Pop Culture

Mona Lisa never left the public imagination, but she became a veritable 21st century sensation with the release of American author Dan Brown’s 2003 fictitious mystery-thriller The Da Vinci Code. Decried as blasphemous by Christian leaders around the world, the novel sold over 80 million copies.

In the novel, the second of the series following Harvard “symbologist” Robert Langdon, Brown claims Leonardo painted Mona Lisa as androgynous in rejection of the “sacred feminine,” as part of a wider conspiracy conducted by the Catholic Church to hide the alleged offspring of Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalene.

While the book was dismissed as “a big farce,” it clearly tapped into a “growing public fascination with the origins of Christianity,” noted Laurie Goodstein, correspondent at The New York Times. “Leonardo’s greatest works were the fruit of his engagement with religious subjects, entrusted to him by some of the Renaissance’s most exacting patrons of sacred art,” reminds art historian Elizabeth Lev in the Catholic Herald.

“[Brown] is responsible for the idea that there are hidden codes, messages, mystic geometries, disguised words, and esoteric numbers in Renaissance paintings,” says Martin Kemp, one of the world’s leading experts on Leonardo. Actor Tom Hanks, who played protagonist Langdon in film adaptations, himself admits, “The Da Vinci Code was hooey.”

While the Dan Brown fad passed, the fascination with the Mona Lisa endures. In 2018, the American multi-millionaire power-couple, Beyoncé and Jay-Z staged their music video Apeshit within the Louvre. Amassing 270 million views on YouTube, as of 2023, the video propelled the Louvre’s annual attendance to a record 10 million visitors.

In Apeshit, the then-multi-millionaire pair dance and lounge within the museum, claiming space for themselves in an institution historically reserved for a white elite. The video contrasts the black bodies of dancers with the static images of European nobility.

A descendent of slaves, Houston-born Beyoncé sings “I can’t believe we made it / This is what we’re thankful for.” While ostensibly empowering, the anti-colonial message raises difficult questions about status as Beyoncé suggests she has only earned her place at the Louvre with wealth.

Elitism

Who is the Mona Lisa for? Is this portrait the apotheosis of human talent or a symbol of a stagnant and undying global aristocracy?

In 2021, an online petition demanded the then-world’s richest man, “Jeff Bezos to buy and eat the Mona Lisa.” It’s a poetic thought to imagine the multi-billionaire Amazon founder cursed to digest the world’s most valuable painting. Two friends had started the idea as a joke, but the viral petition hit a real concern over rising inequality.

A year later, the Mona Lisa — protected by glass casing — was smeared with cake in a pattern of headline-grabbing art-attacks by environmental activists. The protestor shouted, “There are people who are destroying the Earth. Think about it. Artists tell you: think of the Earth. That’s why I did this.”

During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the French government appeared unconcerned about the living people who gave Mona Lisa her voice. Either self-employed or under short-term contract, most of France’s cultural guides (guide-conférenciers) were considered ineligible for financial assistance. According to trade unions and associations, only 23% had any access to unemployment insurance.

On July 6th of 2020, some 200 tour guides gathered at the Louvre upon the museum’s reopening, as part of a national protest over the government’s distribution of COVID-19 funds. Holding images of the Mona Lisa, guides argued they were being silenced. “Heritage is the wealth of France. But who will present it? Who will advertise France?” asked Sophie Bigogne, a guide-lecturer of 35 years.

Despite repeated assurances from the government, the situation did not improve. The estimated number of tour guides in France dropped from 7,000 in March of 2020 to 4,500 the following year. Though visitors have returned, it remains unclear how the industry will recover. “Our profession is threatened with extinction,” warns guide Chloé Merccion.

Recently, Mona Lisa was attacked again amidst a farmer protest over regulations and subsidies. Armed with pumpkin soup, members of the activist collective Riposte Alimentaire (“Food Counterattack”) shouted, “What is more important? Art or the right to have a healthy and sustainable food system?”

Consumerism

Even today, when we can access her image within seconds online, the Mona Lisa beckons to be experienced in person, unmediated by screen. “The painting is a pilgrimage piece,” says museum consultant Gail Dexter Lord. Arts journalist Christina Ruiz describes it as “a quasi-sacred experience at a time when universal faith has been overtaken by consumerism.”

Back in 2017, American artist Jeff Koons was tapped to create a collection with the French luxury fashion house Louis Vuitton. “I can put my work on the street!” Koons exclaimed, hoping customers will appreciate his “effort to erase the hierarchy attached to fine art and old masters.”

The late founder of Off-White, Virgil Abloh also featured the Mona Lisa in his collections, including a collaboration with the Swedish furniture company Ikea. He explained, “It’s a crucial part of my overall body of work to prove that any place, no matter how exclusive it seems, is accessible to everyone.”

Despite noble intention, fashion director and critic Vanessa Friedman laments, “consumers are being introduced to great art as if it is disposable.” But perhaps it’s not so simple.

Fame & Vanity

The Mona Lisa has outgrown the Louvre — the world’s only major museum with repurposed architecture. Only 30,000 people per day can now enter the medieval fortress to ensure a “moment of pleasure” for visitors.

Does Mona Lisa still deserve her attention? Or is she, as art critic Jason Farago poses, “the Kim Kardashian of 16th-century Italian portraiture”? Is that her appeal, as a reimagined influencer, an icon of 21st century vanity, with poised posture and perfect smile?

Lady Lisa’s eyes follow viewers around the room, an arresting gaze which feeds our craving for attention. “How we perceive ourselves or desire to be perceived is a defining feature of mankind that persists to this day,” write authors Arne Flaten and Stephanie Miller.

In hindsight, the Mona Lisa was destined for fame. Professor of comparative European history at Queen Mary and Westfield College, Donald Sassoon writes, “Painted by a genius, bought by a king, set in the heart of Paris, worshipped by intellectuals, kidnapped by an Italian, sent up by the avant-garde, chosen to represent France by de Gaulle, worshipped by the Americans and the Japanese and backed by a global advertising industry.”

Even now, after countless hours of pouring myself into research, reproductions and parody, I can’t decide if I love or hate Mona Lisa. As Bron says in Glass Onion, “This simply thing that you thought you were looking at, it suddenly takes on layers and depth so complex, it gives you vertigo.” Like a magnet, she simultaneously repels and attracts. I suppose that’s her power.