Kent Monkman is Decolonizing Gender

Cree artist Kent Monkman seeks to decolonize gender with his work about colonization, resilience, and sexuality.

Cover photo: Wedding at Sodom, acrylic on canvas, by Kent Monkman (2017). Via the artist’s website.

This article is part of my 30 Living Queer Artists Worth Celebrating in 2019 series. June is Pride Month, commemorating the international gay rights movement that began June 28th, 1969, with the Stonewall riots of New York. 2019 marks the 50th anniversary of the event. I’m celebrating all month long!

WARNING: The following article features and/or discusses graphic nudity, colonization, rape, abduction, and sex.

Kent Monkman

Kent Monkman is a multidisciplinary Canadian artist of Cree descent who creates art about colonization, resilience, and sexuality. Drawing from the experiences of indigenous people, Monkman’s maximalist tableaus often depict historical — though exaggerated — events.

Monkman makes use of numerous references to art history in his work, specifically European Modernism, which coincide with the century-long maltreatment of indigenous people. Through his paintings, installations, and performances, Monkman hopes to educate the public about the plight and resilience of indigenous people.

Colonialism

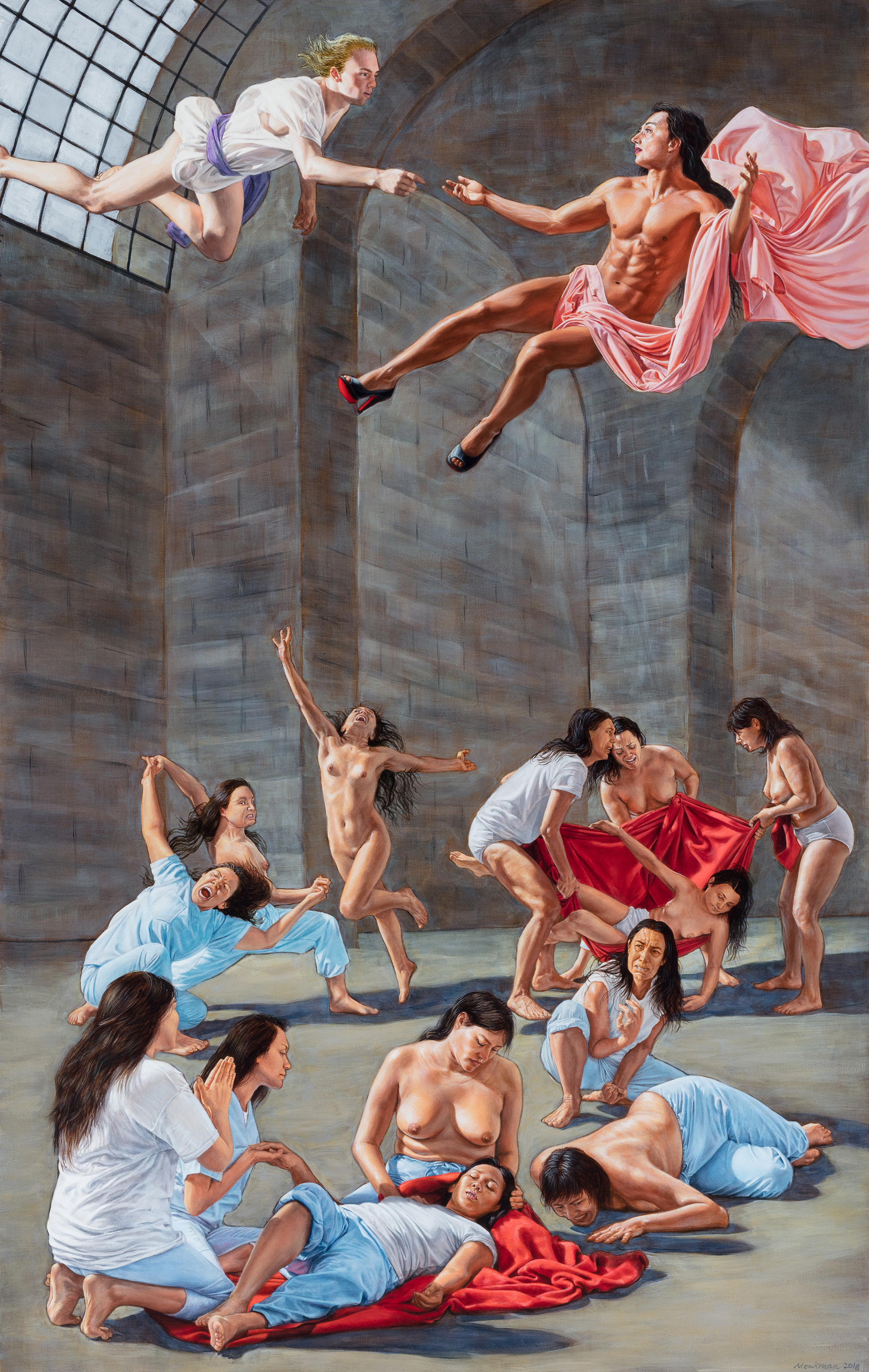

The vast majority of Monkman’s work revolves around the colonization of indigenous people. Monkman made this theme most explicit in his series Shame and Prejudice, which he created to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the establishment of the Canadian Confederation in 2017. Monkman went viral online with his painting The Scream, which references the Canadian government’s abduction of indigenous children in the 20th century.

Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families and placed in non-indigenous homes or foster care through a series of policies now called the Sixties Scoop. They were also forced to attend Indian Residential Schools where they were taught Christian values, as well as reportedly beaten and raped.

Monkman recreates the abduction in a modern setting with contemporary clothing. The resulting artwork is unflinching and completely devastating. Assisted by armed Royal Canadian Mounted Police, nuns and priests tear children away from their mothers. The title, The Scream — which references Norwegian painter Edvard Munch — captures this visceral loss.

This shameful treatment of indigenous people throughout history is rarely taught. “I want Canadians to learn about indigenous experience. The founding myths of both Canada and the US are flawed in that they don’t really incorporate the real story and the truth of what happened. There’s a lot of falsehoods in the creation of these myths about Canada and the US,” explains Monkman.

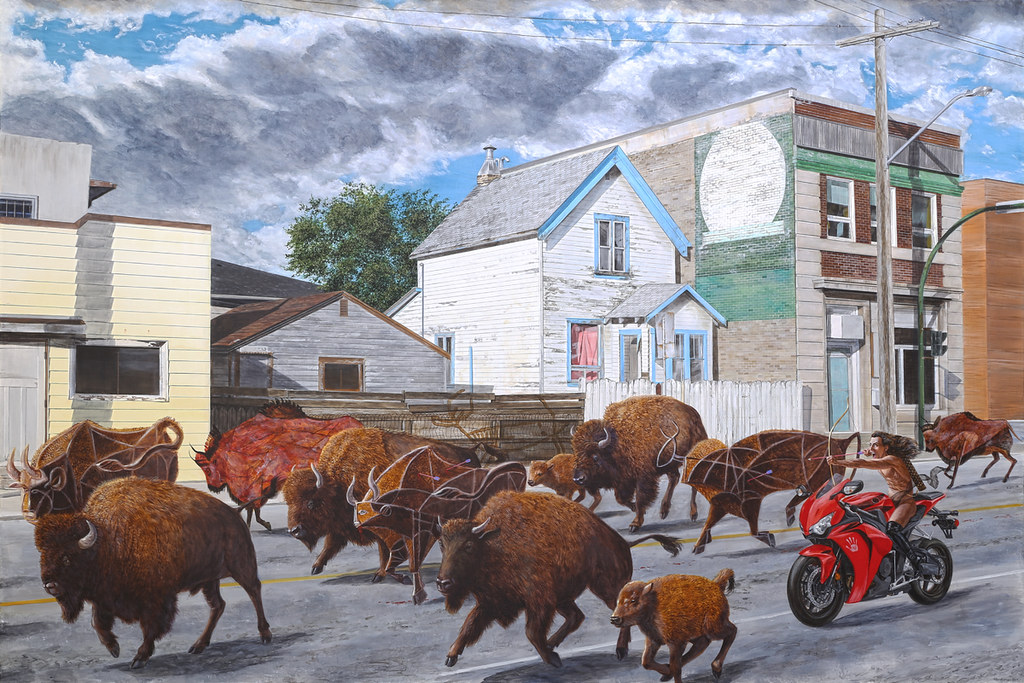

The Chase, acrylic on canvas, by Kent Monkman (2014). Via the artist’s website.

European Modernism

Monkman often incorporates references from European modernism into his work, most frequently cubism. Monkman uses these references to flatten time and space and to bring attention to the enduring struggles of indigenous people.

In his 2014 painting The Chase, Monkman’s alter-ego Miss Chief rides a motorcycle with a bow and arrow, pursuing a herd of bison. Several bulls are directly taken from the work of Spanish painter Pablo Picasso.

The stampede also includes bulls from the prehistoric Lascaux Cave in France, generally considered the earliest recording of man-made art. Reportedly, when Picasso visited the cave in 1940, he said of modern art, “We have discovered nothing.”

The anachronistic event of The Chase takes place in a contemporary city street. The juxtaposition of the road with the herd of bison is jarring. Monkman notes, “I wanted to re-stage some of these scenes in urban environments, because a lot of indigenous people live in cities. In Canada, more than half are living in cities. And a lot of urban environments are places where Native people once inhabited. This ties back to some of the themes in my current work — this amnesia in the face of modernity.”

The Daddies, acrylic on canvas, by Kent Monkman (2016). Via the artist’s website.

Miss Chief Eagle Testickle

Often featured in Monkman’s art, is his alter-ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, “a time-traveling, shape-shifting, supernatural being who reverses the colonial gaze to challenge received notions of history and Indigenous peoples.” Monkman has incorporated the character of Miss Chief into his paintings, installations, and performances.

Monkman describes Miss Chief “as a sort of gender-bending character, [who] came from the tradition in indigenous cultures having a third gender, male or female, who lived in the opposite gender.” He concludes, “She’s an empowered representation of decolonized sexuality.”

He was inspired by American painter George Catlin, who would include himself in his art. Monkman recalls, “I wanted to create an artistic persona that could rival that of Catlin. So [Miss Chief] was created to reverse the gaze. She looks back at European settlers.”

Miss Chief is the main subject in Monkman’s painting, The Daddies, a near-replica of Robert Harris’s iconic 1884 work, The Fathers of Confederation. Monkman explains, “In this painting of the Fathers of Confederation, which I call The Daddies, I sat Miss Chief on a little stool in the front of the composition as a way to insert an indigenous point of view or an indigenous perspective into this meeting where Canada was carved up into the provinces.”

Wild Flowers of North America, acrylic on canvas, by Kent Monkman (2017). Via the artist’s website.

Two Spirits

Much of Monkman’s oeuvre is dedicated to the empowerment of indigenous people through the illustration of native people and their native traditions. Prior to colonization, indigenous people held great respect for intersex, androgynous, and gender-nonconforming people. Today, these people are known under the umbrella term “two-spirits” which bridges this concept between various indigenous nations.

Many two-spirits are visible in Monkman’s series, The Rendezvous, inspired by Alfred Jacob Miller’s depictions of the titular event. The mid-1820s Rendezvous was an annual event in which fur trappers and indigenous people traded goods. The Rendezvous was a boisterous celebration. American writer and historian, Washington Irving described the recurring event as a “saturnalia among the mountains.”

“This subject appealed to me because it was before the colonial policies had really reached the far West. I wanted to focus on the strength of indigenous people in that period,” Monkman recalls. In the series, Monkman depicts a jubilant period before imperialism and the subsequent colonization of gender. In Wild Flowers of North America, several two-spirit people are visible. They are open and unashamed, freely participating in the bacchanalia.

Indigenous people are reclaiming agency over their gender. Dozens of two-spirit organizations have formed in North America in recent years. California’s Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirit Powwow is now in its eighth year and draws as many as 4,000 attendees annually.

Assistant professor of American studies and ethnicity at the University of Southern California, and member of the Colville Nation, Chris Finley says, “There’s no way you can talk about colonization without talking about gender and sexuality.”

Vital Attention

As witnessed in 2017, with the construction of the crude oil Dakota Access Pipeline through indigenous territory, it is increasingly vital to bring attention to the struggles of indigenous people.

Kent Monkman continues to create provocative art that seeks to educate and empower. His artwork is challenging the status-quo and changing narratives. Follow him on Instagram.