Focus on Experience

In our digital-obsessed world, experience is more important than ever.

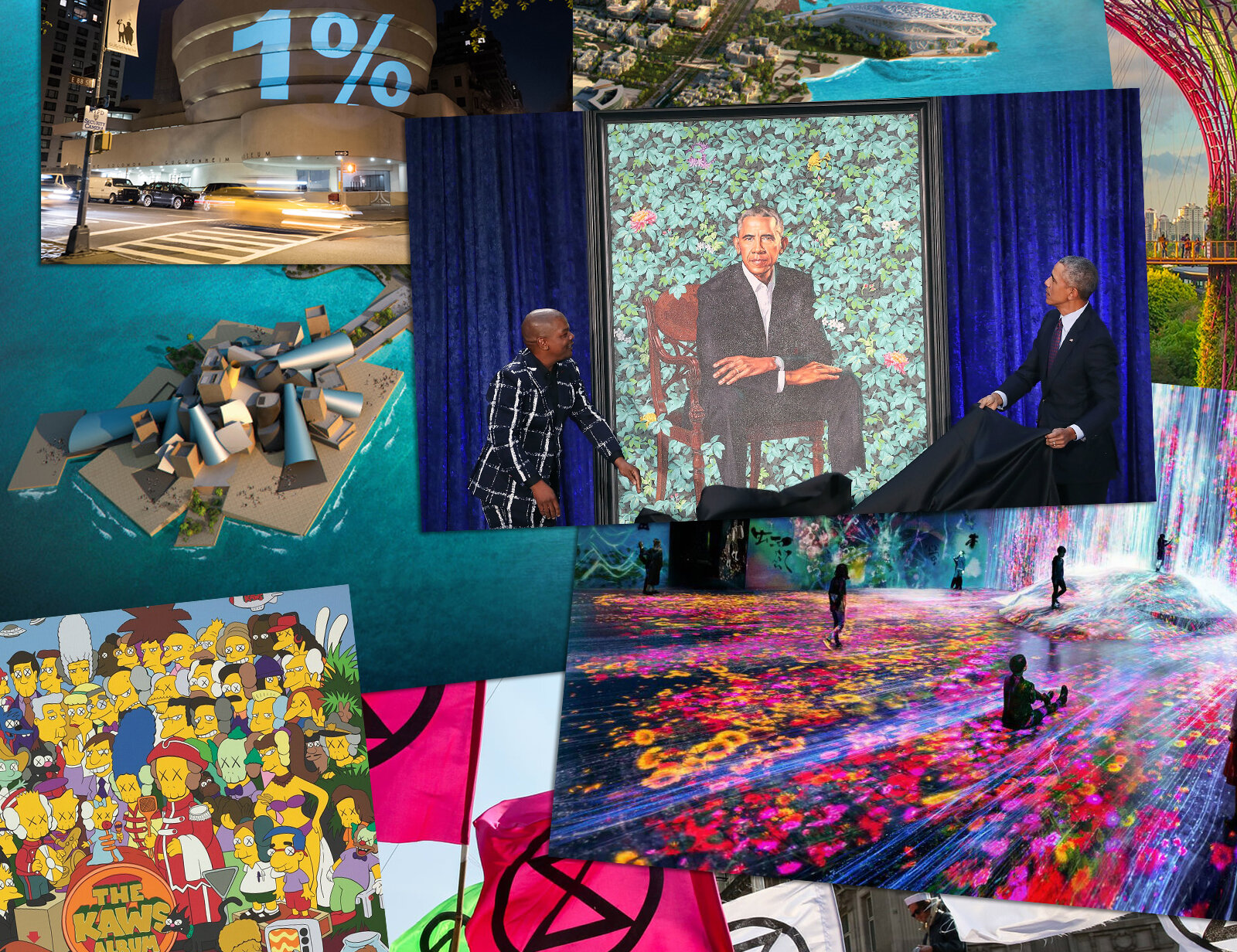

Cover photo: A collage of the past decade, featuring highlights in art news (2019).

It’s been an eventful decade. This article is part of a series about five of the most noticeable shifts in art, how we enjoy it, who creates it, who buys it, who funds it, and the content it reflects.

Into the Real World

Among the most obvious shifts in the art world is the renewed focus on experience. Every day we are inundated by images on our televisions, computers, and phones. This over-saturation has left us craving a more immersive experience offline. This decade, performance, installation, and interactive art have reached unprecedented popularity.

One of the most memorable exhibitions of 2010 was The Artist is Present at the MoMA in New York. Performance artist Marina Abramović sat at a table, where she invited attendees to gaze into her eyes for any amount of time they wished. One visitor — who had sat for thirty minutes — wrote how mesmerized she was by the intimacy “between two total strangers.” Many broke into tears. The exhibition broke attendance records, drawing 850,000 visitors.

Then came October 6th, 2010, one of the most important days of the decade: the day that saw the launch of the photo sharing app Instagram. The app had grown to 1 million users by December and now — a full decade later — Instagram has amassed 1 billion users. The seismic shift Instagram has caused in the world cannot be overstated as it has dramatically changed the way we consume and interact with art (and everything else).

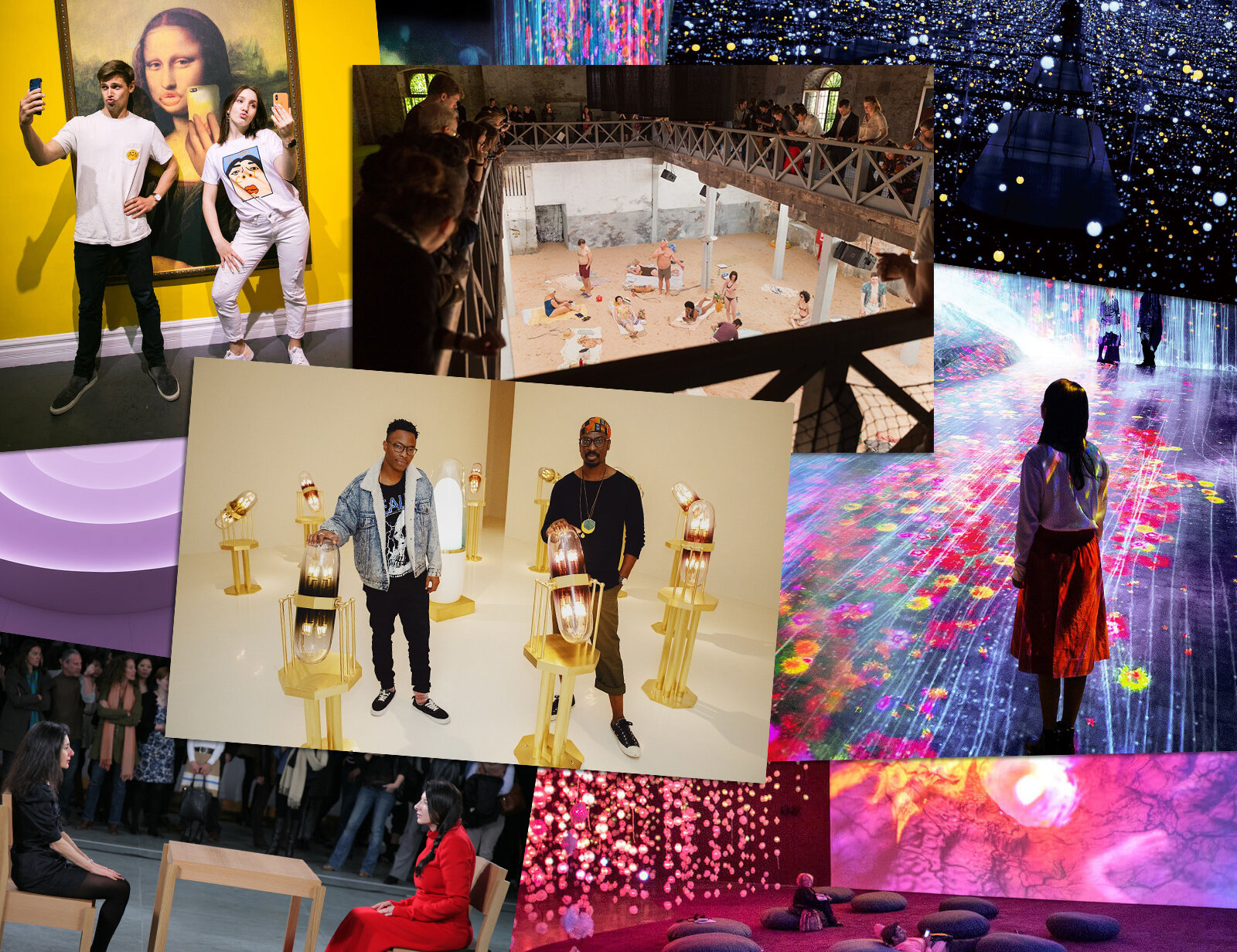

Instagram has fomented an insatiable desire for interaction with and documentation of our experiences with art. It is single-handedly responsible for the rise of the pop-up gallery industry, “selfie-factories” in which guests are encouraged to take photos of themselves in decorated environments.

“I don’t think there’s anything wrong with people taking selfies at museums – the challenge is when people become obsessed with staring at their screens as opposed to experiencing life,” notes Tommy Honton, co-founder of The Museum of Selfies in Los Angeles. The gallery was opened as a temporary pop-up in 2018, but it was relocated to a permanent site before the end of the year.

Installation Art

The immersive Mori Building Digital Art Museum: Epson teamLab Borderless in Tokyo opened in 2018, billing itself as the world’s first digital art museum. Viewers may find teamLab derivative of Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama who was among the pioneers of installation art in the 1970s.

As they say, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Kusama’s work has now reached new heights. In 2017, The Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. drew its highest attendance in 40 years as 160,000 visitors rushed to see Kusama’s Infinity Rooms. Her popularity shows no signs of waning in the next few years.

Installation art — which is by definition multimedia — offers increased engagement with the senses, offering visual, auditory, and sometimes even tactile stimuli. There is a profound lack of academic work examining the effects of installation art, but an exploratory psychological study published in 2018 established the groundwork that installation art produces “distinct emotional and evaluative responses” in viewers and that those “who evaluated the art as happy tended to have a positive viewing experience, whereas those reporting sadness had generally negative evaluations.”

People like installations that make them happy, and they dislike installations that make them sad. With museum curators so focused on visitor attendance, how will this affect the art that is exhibited and created? Will visitors and curators alike reject art that is more challenging in favor of colorful backdrops? This is certainly the case in pop-up galleries, which appeal to lowest common denominator tastes like the Museum of Ice Cream, Museum of Illusions, or Color Factory. Can anyone have a meaningful experience in these spaces?

Aesthetics

A journal article written in 2015 by Emeritus Psychology Professor Vladimir J. Konečni, proposes that “some installations are far more likely than paintings to induce aesthetic awe in spectators by virtue of their far greater amenability” to stimuli like “physical grandeur, rarity, and novelty” which Professor Konečni asserts are likely derived from “evolutionary origins”. In layman’s terms, Konečni posits that installation art is uniquely suited to satisfy our evolved aesthetic tastes.

Whatever the reasons, installation art’s success is undeniable. Artists like American James Turell and Swiss Pipilotti Rist have produced record-breaking shows. “With my exhibitions I want to provide a stage and let the visitors become the actors,” proclaims Rist. Visitors are eager to oblige. Museums of all disciplines have embraced interactive technology like responsive displays and virtual reality.

Participation

In 2019 the Lithuanian Pavilion was awarded the highest honor of Golden Lion at the 58th edition of the Venice Biennale. The pavilion housed Sun & Sea (Marina), an enchanting hour-ish-long opera staged on a man-made beach inside a warehouse. The opera — created by composer Lina Lapelyte, librettist Vaiva Grainytė, and director Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė — became a surprise hit, drawing nearly 90,000 visitors (I waited for an hour to witness the ultra-popular performance).

The performance about leisure and ensuing climate change was languishing, engrossing, and vital but what really made the artwork stand out was the fact that visitors were invited to sign up and participate, to lounge on the sand as the actors sang their songs. Sun & Sea (Marina) blurred the line between art and audience. As the official website of the Venice Biennale states, “The jury was impressed with the […] Pavilion’s engagement with the city of Venice and its inhabitants.”

The Dallas Museum of Art in Texas recently opened a new exhibit, Speechless, that was designed specifically for interaction. “This exhibition is about blurring the boundaries between senses, media, disciplines, and environments to encourage visitors to interact and communicate through design,” explains curator Sarah Schleuning. Schleuning was also responsible for bringing Dior: From Paris to the World to the DMA which became the museum’s most attended ticketed special exhibition of the decade.

One of the artists participating in the new exhibit, Swiss-based Ini Archibong explains about his work Theoracle, “It was designed to be inviting; for people to put their hands on.” Is this art’s future? Painting is certainly not dead, but the nature of art will continue to evolve as artists embrace and push other mediums to new limits.