Film Club: René Magritte and the Surrealism of Squid Game

Squid Game offers a refreshing surrealist interpretation of capitalism’s mundane horror.

Cover photo: Seong Gi-hun holds his umbrella-imprinted dalgona in the air, Squid Game, episode 3, The Man with the Umbrella, directed by Hwang Dong-hyuk (2021). Via Netflix and The New York Times.

WARNING: Graphic images, blood, death, suicide, and spoilers!

Watch my video essay on YouTube.

Global Phenomenon

The Netflix-produced Korean drama Squid Game has captured the world’s attention, rising to become the company’s most popular show ever. The terror of the series transcends language, as players of the titular game risk everything in hopes of winning a life-changing cash prize.

What is it about the design of Squid Game that has made it such an international success? The answer: a refreshing surrealist interpretation of capitalism’s mundane horror.

Ultrarealism

Upon winning the Squid Game, the Front Man — a previous winner by the name of Hwang In-ho — tells victor Seong Gi-hun, “Just think of it as a dream.”

And what are dreams if not “concealed realizations of repressed desires”? Such an idea was posed by the famed psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, whose early 20th century writings were an inspiration to an emerging group of artists known as Surrealists.

Surrealism was born out of the trauma of World War I. It was a creative revolt against the rationalism that lead to the deaths of millions. The Surrealists believed that the only antidote to a grim war-torn reality was one envisaged by dreams.

In a 1947 interview, the Belgian artist René Magritte explained, “I live in a very unpleasant world because of its routine ugliness. That’s why my painting is a battle, or rather a counter-offensive. The world is so strange.”

Magritte’s childhood was marred by his mother’s suicide. As an adult, during World War II, he was faced with poverty, resorting to the forgery of banknotes.

“The surreal is not to be confused with the desire for an imaginary world,” Magritte clarified in 1962. “The surreal, or surreality, is reality stripped of the banal or extraordinary meaning attached to it. The surreal is reality which has not been separated from its mystery.”

Surrealism can be translated as ultrarealism. In this way, we can understand the series of Squid Game not as a parody or an exaggeration of reality, but a more true reflection of our world, one which strips back all pretense.

“I wanted to write a story that was an allegory or fable about modern capitalist society, something that depicts an extreme competition, somewhat like the extreme competition of life,” explains Hwang Dong-hyuk, the writer and director behind the creation of Squid Game.

Squid Game was inspired by Hwang’s own economic woes following the global financial crisis of 2008, which forced him to ask, “If there was a survival game like these in reality, I wondered, would I join it to make money for my family?”

In the series, the Squid Game is intended as a final refuge from the capitalist system that has left participants behind. The Front Man explains, “Players compete in a fair game under the same conditions. These people suffered from inequality and discrimination out in the world, and we offer them one last chance to fight on equal footing and win.”

“The show is motivated by a simple idea. We are fighting for our lives in very unequal circumstances,” reveals Hwang. In the words of columnist Frank Bruni, Hwang depicts “life as a sadistic lottery and poverty as a hopeless torture chamber”.

“That this vision appeals to so many viewers, especially young ones, suggests a chilling and bleak perspective,” Bruni argues. According to Hwang, the 2016 election of U.S. President Donald Trump — a popular reality television host — validated his concept of capitalism as a fatal game show. President Trump was not leading a nation, says Hwang, but instead “giving people horror.”

This socio-political brand of horror has become a craving for the 21st century audience. Films like The Hunger Games (2012-2015), Sorry to Bother You (2018), and Parasite (2019) have revealed an insatiable appetite for — in the words of Magritte — “revolts against the execrable conditions of life and … attacks [on] the dubious ideas of morality, religion, country and aesthetics imposed … by the capitalist world.”

Once a member of the Belgian Communist Party, Magritte was a proud anti-capitalist. “The true value of art is a function of its power as a liberating revelation,” he declared. Artists, according to him, “must fight against the banal reality wrought through centuries of worshipping money”.

Both Magritte’s style and philosophy influence Squid Game. The surrealism heightens the violence of the series and elucidates the horror of daily life, not only in South Korea but all nations dominated by global capital.

“The art teams had to think like a designer who created the games,” explains art director Chae Kyoung-sun. “Aesthetically speaking, we created the places and displays trying to make the viewers think about the hidden intentions of Squid Game with us.” She exclaims, “As an art director, this show inspired me to use my imagination to its fullest.”

Surrealism, as declares curator Stephanie D’Alessandro, allows us “to interrogate our circumstances, wake ourselves up from the habits and customs that we are almost unaware of in our daily lives, and in doing so, consider an alternate view, [and to] open ourselves to possibility. Surrealism offers a revolution.”

Let’s take a look at the surrealist techniques Squid Game employs, pioneered by René Magritte.

Screenshot: Detective Hwang Jun-ho searches his brother’s apartment, from Squid Game, episode 2, Hell, directed by Hwang Dong-hyuk (2021).

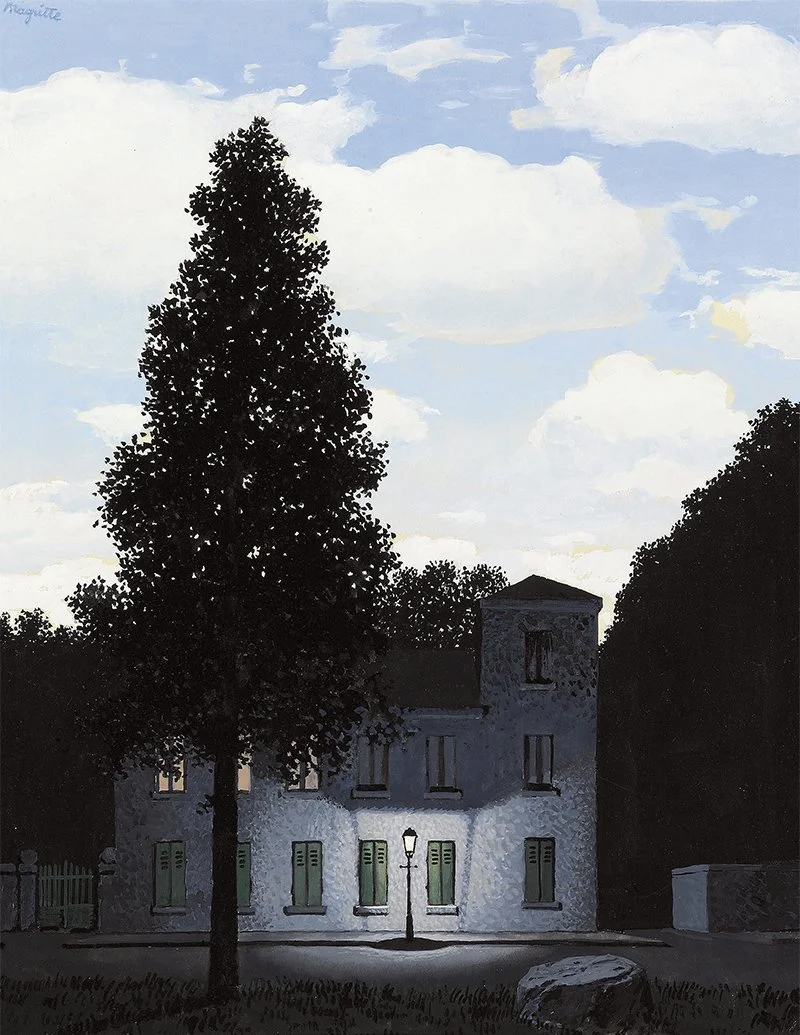

L’Empire des lumières (The Empire of Light), gouache on paper, by René Magritte (1947). Via Christies.

Dépaysement

René Magritte’s influence is made explicit in the second episode, titled Hell. Detective Hwang Jun-ho visits his brother’s apartment in search of clues to his whereabouts, unaware that In-ho is in fact the game’s supervisor, known as the Front Man. The space features several books devoted to European artists and philosophers. Not one, but three reproductions of Magritte’s Empire of Light paintings are visible.

Empire of Light was one of Magritte’s most popular concepts; he created twenty-seven variations. In this series, which he first began in the 1940s, Magritte depicts a paradoxical image of a nocturnal street scene with a sky awash in sunlight. Separately, day and night are mundane, but together they evoke a magical, even unsettling, atmosphere.

This is a technique known as dépaysement — literally “un-home” — in which Magritte places familiar objects in unfamiliar settings, creating a mood of disorientation. Writes Park Sun-ae for Kookmin University Press, “Magritte shocks us by presenting new meanings in contrast to our commonly accepted ideas.”

“I got the idea that night and day exist together, that they are one,” explained Magritte. And indeed, “in the world night always exists at the same time as day. (Just as sadness always exists in some people at the same time as happiness in others.)”

The presence of books about European art and philosophy telegraphs In-ho as the Front Man, as he clearly has an interest in Western culture. The only diegetic tracks played in the series are a cover of American singer Frank Sinatra’s Fly Me to the Moon and The Blue Danube by Austrian composer Johann Strauss.

The presence of Magritte’s Empire of Light foreshadows — pun intended — Hwang In-ho’s identity. Bastien Alleaume writes for Artmajeur, “Its symbolic force is obvious: it is the coexistence of darkness and light, of good and evil, of the occult and the sacred. As if to testify to the internal evolution of a character, who goes from prey to executioner, from victim to persecutor, from fragile player to cruel supervisor. This artwork disrupts the fundamental organizing principle of life, while provoking confusion and unease.”

At a metatextual level, Squid Game employs dépaysement as the core concept of the series, with the juxtaposition of carefree children’s games with mass death. This perversion of nostalgia and innocence heightens the violence. As Magritte notes, “Charm and menace can enhance each other through their union.”

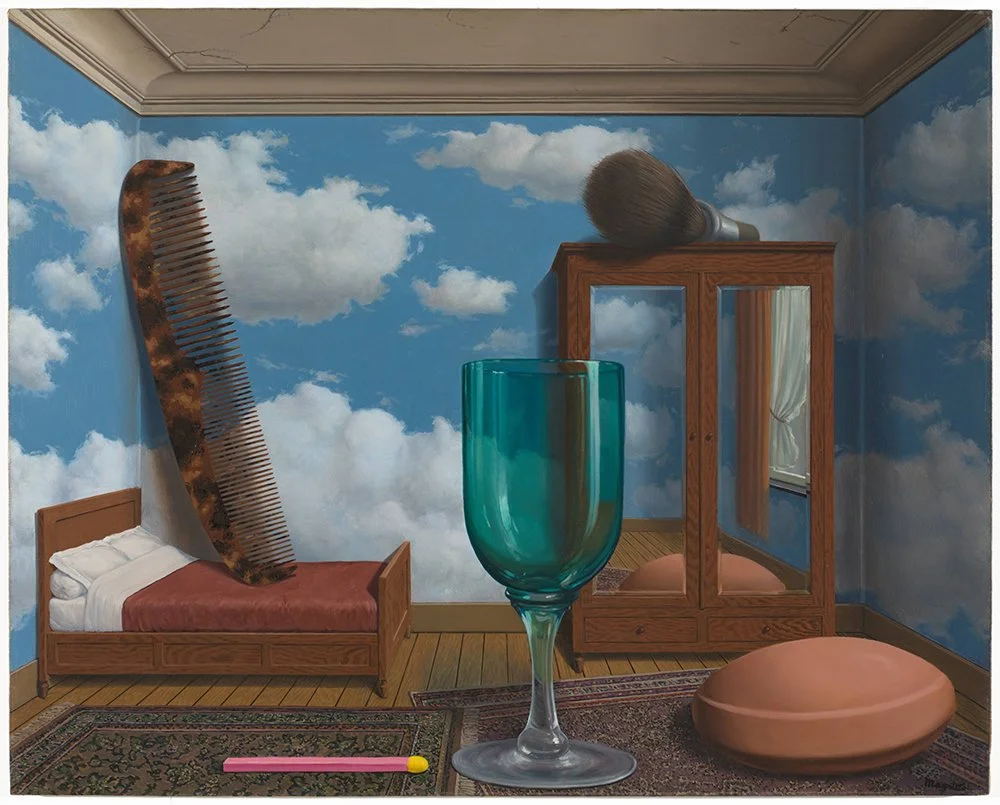

Les valeurs personnelles (Personal Values), oil on canvas, by René Magritte (1952). Via SFMoMA.

Screenshot: Squid Game participants enter Round 2, set in a giant playground, from Squid Game, episode 3, The Man with the Umbrella, directed by Hwang Dong-hyuk (2021).

Hypertrophy

When participants are escorted into the arena for Round 2 of the Squid Game, they find themselves in a playground filled with giant equipment. Unnerved, Gi-hun immediately wonders, “Why the hell is this playground so huge?”

Lee Jung-jae, the actor who plays Gi-hun, notes, “In that scene, we were playing a survival game to win in that innocent childlike playground. That itself had feelings of some kind of conceptual art.”

The set recalls Magritte’s 1952 painting Personal Values. In this work, Magritte employs one of his most commonly used techniques, known as hypertrophy. Hypertrophy is a deliberate distortion of size, or a “jarring alteration of scale among familiar objects that creates an unnerving effect.”

In this painting, Magritte depicts a room full of ill-sized objects. Writer Regina Marler observes, “a lusciously painted tortoiseshell comb, a vivid blue-green glass, a gargantuan bar of soap, and other personal items dwarf a modest bedroom.”

Personal Values made Magritte’s own art dealer, Alexander Iolas, sick. “It leaves me helpless, it puzzles me, it makes me feel confused and I don’t know if I like it,” he complained. In response, Magritte argued, “A picture which is really alive should make the spectator feel ill.”

This is the same effect elicited by Squid Game which juxtaposes the carelessness of childhood with the savagery of competition. “When I first started watching it,” notes Kyung Hyun Kim, a filmmaker and professor of visual and East Asian studies at the University of California Irvine, “I was disgusted because it felt to me a violation of … an innocent memory”.

“That experience of changes in scale is a defining element in the set design for the second game,” explains Chae. Enlarging the playground makes the adult participants feel small and powerless. In other scenes, players are terrorized by a gargantuan doll or inspired by an enourmous piggy-bank.

Early in his career, Magritte himself worked as a wallpaper designer and commercial artist. According to the auction house Christie’s, “perfect white clouds floating amidst a perfect blue sky have become one of the artist’s most signature motifs used in a variety of ways throughout his art, a banal yet enigmatic, intangible part of the everyday world.”

Surrounded by clouds, participants are reminded of their own sunny days spent playing outside with friends. Painted on the walls however, the clouds are instead ominous, a vivid reminder of the participants’ enclosure.

Screenshot: Seong Gi-hun’s umbrella-imprinted dalgona, from Squid Game, episode 3, The Man with the Umbrella, directed by Hwang Dong-hyuk (2021).

Les vacanes de Hegel (Hegel’s Holiday), oil on canvas, by René Magritte (1958). Via Christies.

Synthesis

In his 1958 painting Hegel’s Holiday, Magritte represented a glass of water resting atop a floating umbrella. In a letter, he explained its genius, “two opposite functions—at one and the same time not wanting water (rejecting it) and wanting it (containing water).” Inspired by the German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel, Magritte combines a thesis and antithesis to produce a synthesis.

Of Magritte, art critic Suzi Gablik observes, “His images incorporate a dialectical process, based on paradox, which corresponds to the unstable, and therefore indefinable, nature of the universe. Thesis and antithesis are selected in such a way as to produce a synthesis which involves a contradiction and actively suggests the paradoxical matrix from which all experience springs.”

Both water and umbrellas are recurring motifs throughout Squid Game, emphasizing the conflict between humanity and wealth.

Rain accompanies the drama’s most emotional moments. It first rains in the series when Sang-woo calls his mother in attempt to tell her goodbye as he plans to commit suicide. He lays drenched in a bathtub as he inhales carbon monoxide, interrupted by an invitation to return to the game. Later, it rains during the final round, when he decides to forfeit his life.

As the weather changes, one of the VIPs invokes the Chinese poet Du Fu, “Good rain knows the best time to fall.” He omits the rest of the poem, including the lines “Wind-borne, it steals softly into the night, nourishing, enriching, delicate, and soundless.”

Squid Game posits wealth as a hollow nourishment, which may release participants from their debts. This is compared to the enriching personal relationships lost throughout the game.

In the fifth round, a game of marbles, participants play in pairs and it is revealed that only one may survive. Sang-woo betrays Abdul Ali and Ji-yeong sacrifices herself so that Kang Sae-byeok may live.

Player 069 loses his own wife. “How could you call yourselves human?” he demands of his fellow players. “You just killed the person you were closest to in this place because of that money.”

“It’s the cost of everyone who died here,” argues Sang-woo. As an investment banker, he has internalized the logic of capitalism, accepting that it is a zero-sum game. The allure of fortune turns even childhood friends into enemies. In order to maintain an advantage, Sang-woo opted to keep his knowledge of the second round to himself.

When Gi-hun chooses the umbrella during the second round, he explains, “My mom used to scold me for losing my umbrella all the time. In the end, she only gave me broken ones. I always wanted a decent umbrella like the other kids.”

It’s raining when Gi-hun refuses money from his ex-wife’s husband for his mother’s hospital treatment. His daughter runs out with an umbrella and catches Gi-hun assault her step-father. “Do you think money solves everything?” Gi-hun shouts. Ultimately, his pride forces Gi-hun to return to the Squid Game.

This decision costs Gi-hun the precious last few days of his own mother’s life. He returns to find her dead. In trying to have both wealth and humanity, Gi-hun achieves something new. He loses his childhood friend, as well as his mother. He finds no joy in his riches and sacrifices his relationship with his daughter in pursuit of revenge.

Gi-hun is a reluctant winner, whose victory denies the idea of Squid Game — and thus capitalism — as a meritocracy. He is not the smartest, the strongest, or even the kindest. Gi-hun is simply the luckiest. Il-nam allowed Gi-hun to win the round of marbles “because it was fun”, confirming the outcome as arbitrary.

On his deathbed, Il-nam asks to be handed a glass of water. “You know what making money is like,” he says. “Is it ever easy?” While no longer financially in debt, Gi-hun finds himself indebted to all the players who lost their lives.

Gi-hun is both a winner and a loser. He has achieved and lost everything. He is a new being. Hwang confirms that Gi-hun’s dyed hair “represents that he will never be able to go back to his old self.” He is a hollowed being, filled only with rage.

In capitalist systems, wealth comes at the cost of humanity. Where nature, land, and food is privatized, people who own nothing but their body must sell their labor to survive. In a world of abundance, scarcity must be engineered. Magritte himself lamented, “Life is wasted when we make it more terrifying, precisely because it is easy to do so.”